Wednesday, August 14

The World's Top Earning Authors of 2013

Quick blog post today.

I'm in the middle of polishing a story that's almost ready to be sent off. The love-hate relationship I have with my manuscripts has veered over to the hate side of things and I just-want-to-get-the-bloody-thing-done! It's what comes from going over it about a billion times.

I used to feel guilty about hating my manuscript--the emotion only lasts for a while, after it has been out to door for about a week I'll love it again--until Stephen King admitted in, On Writing, that he sometimes hates his manuscripts too.

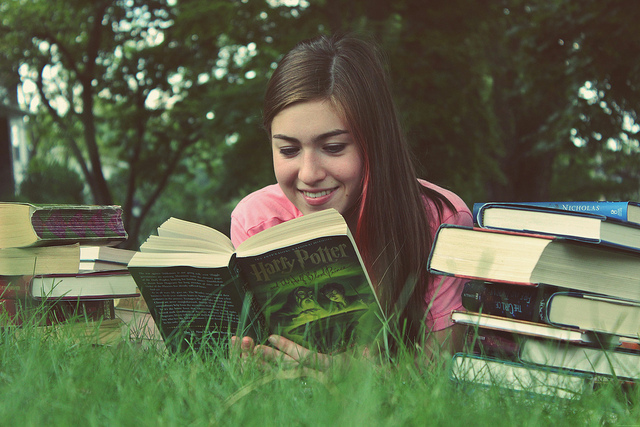

In any case, I'll leave you with what I call 'the dream list.' Personally, I'm hoping to be #17 one day. #1 would be great but then my life wouldn't be my own, I'd have to dress up and put on makeup to go to the corner store for milk! #17 has millions of dollars and anonymity. Kudos.

From Forbes: The World's Top-Earning Authors.

1. E.L. James, $95 million

2. James Patterson, $91 million

3. Suzanne Collins, $55 million

4. Bill O'Reilly, $28 million

5. Danielle Steel, $26 million

6. Jeff Kinney, $24 million

7. Janet Evanovich, $24 million

8. Nora Roberts, $23 million

9. Dan Brown, $22 million

10. Stephen King, $20 million

11. Dean Koontz, $20 million

12. John Grisham, $18 million

13. David Balacci, $15 million

14. Rick Riordan, $14 million

15. J.K. Rowling, $13 million

16. George R.R. Martin, $12 million

Photo credit: "Winter Meal" by Jan Tik under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0.

Monday, August 12

Amazon Sales Ranking Explained

Theresa Ragan has written the most useful article I've read concerning what Amazon's sales ranking means: Sales Ranking Chart.

Theresa's entire article is well worth the read, but here is an excerpt:

Amazon Bestsellers Rank is the number you find beneath the Product Description. Every book on Amazon has an Amazon Bestsellers Rank. Click on any title and then scroll down until you see it.Once again, Theresa Ragan's article is: Sales Ranking Chart.

March 2013 update: rankings have changed substantially in the past few months and I am making changes to reflect rankings and book sales as information is given to me.

Amazon Best Seller Rank 50,000 to 100,000 - selling close to 1 book a day.

Amazon Best Seller Rank 10,000 to 50,000 - selling 3 to 15 books a day.

Amazon Best Seller Rank 5,500 to 10,000 - selling 15 to 30 books a day.

Amazon Best Seller Rank 3,000 to 5,500 - selling 30 to 50 books a day.

Amazon Best Seller Rank 500 to 3,000 - selling 50 to 200 books a day.

Amazon Best Seller Rank 350 to 500 - selling 200 to 300 books a day.

Amazon Best Seller Rank 100 to 350 - selling 300 to 500 books a day.

Amazon Best Seller Rank 35 to 100 - selling 500 to 1,000 books a day.

Amazon Best Seller Rank 10 to 35 - selling 1,000 to 2,000 books a day.

Amazon Best Seller Rank of 5 to 10 - selling 2,000 to 4,000 books a day.

Amazon Best Seller Rank of 1 to 5 - selling 4,000+ books a day.

I came across Theresa's blog because I've started reading The Naked Truth About Self-Publishing, a book she contributed to. So far it's been informative.

Photo credit: "verfremdeter lavendel" by fRandi-Shooters under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0.

Sunday, August 11

Hugh Howey, Liliana Hart and Matthew Mather: How To Write And Sell Books

Usually I write about how to create the best book one possibly can. Today I want to talk about how to sell the most books one possibly can.

As I've mentioned in other posts, I write under pen names (and, no, +John Ward, I'm not telling you what they are ;) but am now getting to the point that I need to start thinking about how to market them most effectively.

Today I'd like to share with you some of my research. I found it inspirational and thought you might too. Most of what follows is a potluck of opinions from successful authors. I hope that, as I have, you find something in the following to help you in your own journey as an indie author.

(The first two authors I look at were featured on a terrific blog I've just begun following from the Alliance of Independent Authors.)

Hugh Howey

"Hugh Howey is an American author, known for his popular series WOOL, which he independently published through Amazon.com's Kindle Direct Publishing system. (Wikipedia)"The following interview is from: How I Do It: Super Successful Indie Authors Share Their Secrets. This week: Hugh Howey.

Hugh Howey's advice: "Write as if nobody will read it; publish as if everyone will read it."

What was the single best thing you ever did?

"I published. I made each work available, and then I moved on to the next story. I also didn't fall into the trap of falling in love with my first world or first set of characters. It's easy to write sequels for the rest of your life, when no one has read the first book. That leaves you forever marketing your weakest material. Instead, I wrote in a variety of genres and styles and for all ages. When something took off, I concentrated on that."

. . . .

How do you get/stay in creative mode?

I don't wait for inspiration to strike. I sit down every day and work on my story. The creativity comes after you've got a nice sweat beading up on your brow. If you wait until you're in the mood, you'll never get anything done.

How do you prioritise?

I set goals. I want to write 2,000 words a day when I'm starting a draft. When I'm revising, I try to get through three chapters a day. When I'm editing, I aim for fifteen chapters a day. I often exceed my goals, but having them is what gets me cranking in the morning.

Liliana Hart

"Liliana Hart is a USA Today and New York Times Bestselling Author in both the mystery and romance genres. ...The following interview is from: How I Do It: Super Successful Indie Authors Share Their Secrets. This week: Liliana Hart.

"... Since self-publishing in June of 2011, she's sold more than a million ebooks all over the world. ... (lilianaheart.com)"

What's the secret of your success?

Hard work and having new books out on a consistent basis. I write all the time. Once you start self-publishing you have to constantly "feed the beast".

. . . .

Did you get lucky? What happened?

… I honestly think if you keep putting out quality content with a professional package that you’re going to find success. Hard work pays off, and self-publishing is a lot of hard-work, but I wouldn’t have it any other way. I love being in control of my career and being able to make changes if I need to.

Matthew Mather

"Matthew Mather is the best-selling author of CyberStorm, recently acquired for film by 20th Century Fox, and the six-part hit series Atopia Chronicles. He is also a leading member of the world’s cybersecurity community who started out his career working at the McGill Center for Intelligent Machines. (matthewmather.com)"Matthew Mather has developed a system for marketing his books, one he shared with readers for the first time earlier this month in his post: SHAKESPEARE system for helping authors figure out self-publishing.

Matthew Mather's SHAKESPEARE system for self-publishing

Where Hugh Howey and Liliana Hart talked about the key to producing novels, Matthew Mather is focused on marketing the finished product. Rather than stepping through his points one by one I'll let you read his excellent article for yourself and, instead, pick out what I thought were the highlights.

1. Make your protagonist someone your readers can like

MM writes:

"It is critical to create a character that you introduce readers to right away that they can empathize with. People read still primarily because they want to feel an emotional involvement with a character they meet in your writing. Keep this front and center of your mind when writing."

2. Get feedback

MM writes:

"Craigslist and other free online classified ads are the secret weapon for a new authors. It is incredibly difficult to get outside feedback when you are a new writer. My solution? Post an ad saying you’ll pay someone $10 or $20 to read your book and give you honest feedback. Note that this is not for line editing, but for high level feedback to make your story more engaging in an iterative process.

"Bonus: Get 20 people to read your book like this; these people will probably become your biggest promoters and will be happy to write reviews and Facebook and tweet your book when released.

"Free PR – When you release your book, create several press releases about different aspects of the book, what it is about, why people would like it. When you release each of the story segments, put these press releases up on the free press release websites. There are about a dozen high quality free release sites out there. Highlight that the short story that is free that week."

3. Focus on Amazon

MM writes:

"To start, focus only on Amazon. I’m not here to promote Amazon, but the first rule of entrepreneurism is to focus, focus, focus. The large majority of revenue in digital books comes from Amazon, with a small minority coming from all of the other players combined. So when you start, focus on Amazon by itself; getting reviews, getting up in the ranking. By only going on Amazon, you force people to buy from one place and thus drive up your rankings in this one spot. Once you have achieved some success there, expand to other platforms (FYI the easiest way to get on other platforms is just to use Smashwords)."

4. Use Amazon Select

MM writes:

"Use the Amazon Select Program: You can offer your book for $0 (free) for 5 days each 3 months. Used effectively, this is an extremely potent tool for reaching an audience. There are at least 40 websites I use to promote a “free weekend” for my books (email me for a list) – these sites are mostly specific to books that go free on Amazon Select and are mostly free to use for promotion.The above is only a fraction of the advice Matthew Mather gives in his article. Worth the read.

"If you can plan it ahead of time, write out all of the parts of your serialized work ahead of time, and then each two weeks release one of them, promoting it on Amazon select for free and on the promotional websites. I can usually get 4000+ downloads of a free book when I do this."

All the best and happy writing! :-)

Photo credit: "Untitled" by Thomas Leuthard under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0.

Thursday, August 8

Harper's Bazaar Holds A Writing Contest

I don't usually announce writing contests, but this one is from Harper's Bazaar and includes a couple of unusual prizes. Here's the scoop:

"Harper's Bazaar, the luxury fashion magazine, is giving writers a chance to submit a short story in their freshly launched literary prize competition.A weeklong retreat on a private island off the coast of Scotland! That's my kind of writing retreat, though I'd doubt there would be much actual writing.

"Harper's is inviting both published and novice writers to enter a 3,000 word short story on the subject of 'Spring'.

"The winning writer will have the fantastic once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to have their story published in the May 2014 Harper's Bazaar issue and the privilege of choosing a first-edition book from Asprey's Fine and Rare Books Department to the value of £3,000. In addition, the lucky winner will enjoy a weeklong retreat at Eilean Shona House, on the 2,000-acre private island off the coast of Scotland."

Before I leave, here's a bit more about the theme of the contest:

"The theme of inspiring literature is woven throughout the September issue of Harper’s Bazaar with a reprinted Virginia Woolf tale from the Bazaar archives, alongside a fashion piece by contemporary writer Margaret Atwood."Where to submit your manuscript: Send your submission to shortstory@harpersbazaar.co.uk. Contest is closed on December 13, 2013.

Length of manuscript: 3,000 words maximum.

I wish I had a webpage I could direct you to but I heard about this contest from an email Harper's Bazaar sent me. Best wishes!

Photo credit: Copyright © Harper's Bazaar. Used with permission.

Monday, August 5

4 Ways To Create A Strong Antagonist

Janice Hardy's blog, The Other Side of the Story, is wonderful and I recommend it to anyone who asks: Which writing blogs should I follow?

Her recent post, 10 Traits of a Strong Antagonist, is one that helped me make the antagonist of my work-in-progress more three-dimensional, more real. Today I'm going to talk about four points that helped make my story stronger.

Remember: a strong villain/antagonist will help you create a strong protagonist.

(See also: How To Build A Villain, by Jim Butcher)

4 Tips on how to create a strong antagonist:

1. Give the Antagonist a goal

Just like protagonists, antagonists have goals. They want things. They have ambitions and desires. These are the sorts of traits that make your characters jump off the page.

As Donald Maass has said a number of times: Antagonists are heroes of their own journey.

2. Make the antagonist similar to the protagonist

Antagonists and protagonists are often a lot alike except for one vital aspect.

For instance, in the BBC's take on Sherlock Holmes both Holmes and Moriarty are brilliant anti-social types but the key difference is that Sherlock is on the side of the angels. He has formed relationships with people, ordinary people like his roommate and best friend Watson and his landlady Mrs. Hudson. He would give his life for them and nearly does.

Which brings us to ...

3. Make the conflict between the protagonist and antagonist personal

Have the rivalry between the antagonist and protagonist hinge on something personal. As tvtropes.org says:

The Protagonist catches bad guys for a living (usually at a rate of about one a week), but this time, the bad guy has decided that he doesn't like the protagonist. Instead of doing what any sensible psychopath would do and simply toss a grenade in the character's window, the psychopath takes creepy photos of the character's kids, abducts the character's wife, kicks the character's dog, and above all, leaves calling cards and clues to ensure that eventually he'll get caught. The bad guy (often a Big Bad) knows about the protagonist's Fatal Flaw and is more than willing to exploit it. (It's Personal)

4. Make the antagonist at least as complex as your protagonist

Janice Hardy writes:

To keep her from being a two-dimensional cliché, give your antagonist good traits as well as bad. Things that make her interesting and even give her a little redemption. This will help make her unpredictable if once in a while she acts not like a villain, but as a complex and understandable person. She doesn’t always do the bad thing.These are only a few of the many wonderful points Janice covers in her article 10 Traits of a Strong Antagonist.

Photo credit: "Untitled" by martinak15 under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0.

Saturday, August 3

Stephen King On What Makes An Opening Line Great

"An opening line should invite the reader to begin the story. It should say: Listen. Come in here. You want to know about this," Stephen King.Stephen King recently gave an interview in which he spoke about what qualities an opening line should have. It's a wonderful, and wonderfully informative, article, one I encourage you all to read: Why Stephen King Spends 'Months and Even Years' Writing Opening Sentences.

Here are a few tips:

1. Open in the middle of action

King says:

We've all heard the advice writing teachers give: Open a book in the middle of a dramatic or compelling situation, because right away you engage the reader's interest. This is what we call a "hook," and it's true, to a point.

2. Give the reader information about the characters and the story

King writes:

This sentence from James M. Cain's The Postman Always Rings Twice certainly plunges you into a specific time and place, just as something is happening:

"They threw me off the hay truck about noon."Suddenly, you're right inside the story -- the speaker takes a lift on a hay truck and gets found out. But Cain pulls off so much more than a loaded setting -- and the best writers do. This sentence tells you more than you think it tells you. Nobody's riding on the hay truck because they bought a ticket. He's a basically a drifter, someone on the outskirts, someone who's going to steal and filch to get by. So you know a lot about him from the beginning, more than maybe registers in your conscious mind, and you start to get curious.

3. A good first sentence introduces the reader to the writer's style

King writes:

In "They threw me off the hay truck about noon," we can see right away that we're not going to indulge in a lot of foofaraw. There's not going to be much floridity in the language, no persiflage. The narrative vehicle is simple, lean (not to mention that the book you're holding is just 128 pages long). What a beautiful thing -- fast, clean, and deadly, like a bullet. We're intrigued by the promise that we're just going to zoom.

4. A great first sentence introduces the reader to the writer's voice

King writes:

With really good books, a powerful sense of voice is established in the first line. My favorite example is from Douglas Fairbairn's novel, Shoot, which begins with a confrontation in the woods. There are two groups of hunters from different parts of town. One gets shot accidentally, and over time tensions escalate. Later in the book, they meet again in the woods to wage war -- they re-enact Vietnam, essentially. And the story begins this way:

"This is what happened."For me, this has always been the quintessential opening line. It's flat and clean as an affidavit. It establishes just what kind of speaker we're dealing with: someone willing to say, I will tell you the truth. I'll tell you the facts. I'll cut through the bullshit and show you exactly what happened. It suggests that there's an important story here, too, in a way that says to the reader: and you want to know.

A line like "This is what happened," doesn't actually say anything--there's zero action or context -- but it doesn't matter. It's a voice, and an invitation, that's very difficult for me to refuse. It's like finding a good friend who has valuable information to share. Here's somebody, it says, who can provide entertainment, an escape, and maybe even a way of looking at the world that will open your eyes. In fiction, that's irresistible. It's why we read.

5. A good first line will give the writer a way to break into the story

King writes:

I don't have a lot of books where that opening line is poetry or beautiful. Sometimes it's perfectly workman-like. You try to find something that's going to offer that crucial way in, any way in, whatever it is as long as it works. This approach is closer to what worked for in my new book, Doctor Sleep. All I remember is wanting to leapfrog from the timeframe of The Shining into the present by talking about presidents, without using their names. The peanut farmer president, the actor president, the president who played the saxophone, and so on. The sentence is:Although I've quoted extensively from Joe Fassler's interview with Stephen King I have left out far more than I included. As in his book, On Writing, King gives practical, easy to understand, advice on the art and craft of writing. A must read.

On the second day of December, in a year when a Georgia peanut farmer was doing business in the White House, one of Colorado's great resort hotels burned to the ground.It's supposed to do three things. It sets you in time. It sets you in place. And it recalls the ending of the book -- though I don't know it will do much good for people who only saw the movie, because the hotel doesn't burn in the movie. This isn't grand or elegant -- it's a door-opener, it's a table-setter. I was able to take the motif -- chronicle a series of important events quickly by linking them to presidential administrations -- to set the stage and begin the story. There's nothing "big" here. It's just one of those gracenotes you try to put in there so that the narrative has a feeling of balance, and it helped me find my way in.

Photo credit: "around and around" by Robert Couse-Baker under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0.

Wednesday, July 31

Chuck Wendig on Plot, Complication, Conflict and Consequence

Chuck Wendig has written what is, I think, his best post on writing so far, and since he has written quite a few fantastic posts that's saying something. Here's his post (adult language -->): Ten Thoughts On Story.

Chuck Wendig's post has ten points, mine only has five and they don't necessarily map onto his points 1-to-1. In any case, there's a lot of great stuff to cover so let's jump in:

1. The three C's of storytelling: Complication, Conflict and Consequence

Here is how Chuck Wendig describes the essence of storytelling:

"[A] character you like ... wants something ... but can’t have [it] ... and goes on a quest to answer that interrupted desire ..."I put the ellipses in the above quotation because CW refers back to his account of his son's first story. (It's a touching account, I do hope you read CW's article.)

Here's an example of what this looks like:

a. Desire/goal

Protagonist desires something. This something is/becomes the story goal.Example: In Indiana Jones And The Raiders of The Lost Ark Indiana Jones desires the ark.

b. Complication

Something/someone comes into the picture that/who will prevent the protagonist from achieving their desire. Another way of saying this: someone else wants the same thing the protagonist does but only one person can have it.Example: Rene Belloq, a rival archeologist, also desires the ark.

c. Conflict

The protagonist and antagonist are pitched against each other in a series of conflicts.Example: Indiana and Rene enter into a contest, a battle of wits/wills, to find the ark and bring it back to their sponsor/patron.

d. Consequence

The consequence of the conflict. Usually there are three possible outcomes:i. The protagonist achieves his goal/desire.

ii. The antagonist achieves his goal/desire.

iii. No one achieves their goal/desire.

Example: Rene is killed by the thing he wishes to possess, Indiana takes possession of the ark and delivers it to his patron in the US though, as it turns out, the patron is not allowed to keep it.

2. The essence of plot

This is how Chuck Wendig describes plot:

"[T]he actions of many characters hoping to gain what they desire and avoid what they fear and the complications and conflicts that result from those actions. A character-driven story rather than one driven by events."

3. Your character's motives, their stories, are the most compelling

Chuck Wendig uses Star Wars as an example:

"At the end of the day, the big story is subservient to the little one. The Empire and Rebellion are just set dressing for the core conflict of Luke, Leia, and their father. Or the loyalty of Han. "

4. Every character has to want something

Chuck Wendig writes:

"Money? Love? Revenge? Approval of estranged father? High score on rip-off arcade game, Donkey Dong? Motivation is king. It moves the characters through the dangerous world you’ve put before them. It forces them to act when it’s easier not to. It gives them great agency."

5. The scene: Yes, BUT .../No, AND ...

A story is told in scenes. In that sense, scenes are the atoms of story. (Chuck Wendig touches on this point, but I thought I'd expand on it.)

In each scene characters have desires, often conflicting desires, but there will be one thing in particular--some goal--they're working toward. By the end of the scene that goal has either been achieved or not (probably not). If not, then another goal has likely taken its place.

(Making A Scene: Using Conflicts And Setbacks To Create Narrative Drive.)

An easy way of remembering this is: Yes, BUT .../ No, AND ...

Yes, the hero achieves his goal, BUT there is a setback. No, the hero does not achieve his goal AND there is a setback. Here are a few examples from Indiana Jones taken from my article Making A Scene:

Examples:

Conflict: Does Indie find the ark?

Setback: Yes, BUT he is captured, thrown into a pit of snakes, and the antagonist takes the ark.

Conflict: Do Indie and Marion survive the pit of snakes?

Setback: Yes, they use torches to keep the snakes at bay BUT the torches are about to burn out.

Conflict: Do Indie and Marion escape the pit of snakes before their torches burn out?

Setback: Yes, Indie crashes a pillar through a wall providing them a way to escape BUT the room they enter is filled with skeletons that--for Marion at least--seem to come alive.

(A bit later in the film ...)

Conflict: Will Indie commandeer the plane?

Setback: No, AND Indie is spotted crawling up the plane, toward the pilot.

Conflict: Indie and a bad guy fight. Will Indie win?

Setback: Yes, BUT a much bigger man starts a fight with Indie (AND the pilot sees indie and knows he's trying to commandeer the plane).

Conflict: The pilot starts to take pot shots at Indie. Will Indie escape being hit?

Setback: Yes, Indie dodges the pilot's bullets BUT the pilot keeps shooting.

Conflict: Indie is fighting a huge bad guy. It looks like he has no chance of winning. Will Indie, against all odds, win the fight against the Man-Mountain?

Setback: No, Indie is not going to win a fist-fight with the Man-Mountain AND the pilot is still shooting at him.

Scenes are chains of conflicts and setbacks followed, at the end, by some sort of resolution/consequence that (unless it's the end of the story) spawn further conflicts and setbacks.

As I said at the beginning, Chuck Wendig's article (adult language -->), Ten Thoughts On Story, is a must-read.

Photo credit: "Smoking Stonehenge" by Bala Sivakumar under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0.

Tuesday, July 30

Scrivener And Goodreader: How To Get Rid Of Paper Drafts

I don't have a printer.

When I need something printed I go to the print shop across the street. It works fine, for the most part, but I don't like killing trees and it's inconvenient not to be able to print something the moment I need it.

The solution: Scrivener + Goodreader

I use Scrivener.

I used to use MS Word and I was (to put it mildly) reluctant to switch word processors. I'd used Word for a number of years, was very comfortable with it--my quibbles with The Ribbon notwithstanding.

But Scrivener has won me over. Having the ability to, at a glance, see a short one sentence description of not only each section but each scene, being able to set up my project targets (I enter the date I want the manuscript done by, the number of words I'd like it to contain and Scrivener will tell me how many words I have to write that day). I also can specify, for each scene, how many words I'd like it to contain and Scrivener will show me my progress graphically.

And the random name generator: heaven!

Anyway. Suffice it to say that I'm a Scrivener convert. You might be wondering what this has to do with a paperless office. I'm coming to that.

PDFs + Goodreader

Scrivener--like Word--gives you the option to output your work as a PDF.

Goodreader--the app--lets you use your finger, or a stylus, to markup PDF files.

This gives writers the ability to get rid of their printer. Here's how:

1. Output your work from your word processor as a PDF file.That's it!

2. Import it into Goodreader (many people use Dropbox or Google Drive for this),

3. Markup the PDF file with whatever changes you'd like to make,

4. Save the PDF file back to Dropbox, switch back to your word processor,

5. Open up the PDF doc in a separate window and make whatever changes you'd like to your original document.

Perhaps laying it out like that, the five steps, makes it look like a lot of work, but it isn't. Or at least it's a lot less work than printing it out. And it allows one to get rid of paper!

I find this works the best for short stories and novellas, I still print out my novel length stories.

If you'd like to read more about this, here's a great article: The Virtual Red Pen.

More good news: Literature & Latte the creators of Scrivener, may have Scrivener on the iPad in time for NaNo this year!

Photo credit: "melancolia" by paul bica under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0.

Wednesday, July 24

Dean Wesley Smith: How To Write And Have Fun

Another great post from Dean Wesley Smith! This time Dean gives us 10 ways to write and have fun while doing it: The New World of Publishing: Having Fun.

1. Dare to be bad

Problem:

If you find yourself getting halfway through manuscripts then abandoning them perhaps the problem is that you're thinking too much about what other people will think about your manuscript.

Solution:

If that's happening, the solution is to write the kind of story you want to write, no matter what your writer friends will think of it.

In other words:

Follow Heinlein's Rules, just as he wrote them. (Robert Sawyer has written a great blog post about Heinlein's Rules which takes things from a slightly different perspective.)

This means writing a story and sending it out when it's finished. Don't put it through a workshop, just send it out. As Robert Sawyer writes:

"And although many beginners don't believe it, Heinlein is right: if your story is close to publishable, editors will tell you what you have to do to make it salable. Some small-press magazines do this at length, but you'll also get advice from Analog, Asimov's, and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction." (On Writing)Dean Wesley Smith agrees:

"Stop caring what other people think. Stop showing your work to workshops. Just finish and publish and never look at numbers or reviews or anything."

2. Learn what works for you

You've heard this before: Every writer is different, what works for one, often doesn't work for another.

What you might not have heard is that each book is different. Neil Gaiman said this in his wonderful hour-long chat with Connie Willis at World Fantasy 2011 (thanks Kim for the link!).

Learn what works for you, for this story. Be creative and be open to change. And trust yourself.

Problem:

You don't know when to let your stories go and either send them out to editors/publishers or publish them yourself. As a result you hang onto your stories too long, rewriting them until your voice has been written out and the piece has all the interest and vitality of cardboard. Dean says that this strengthens your critical voice and hampers your creative voice.

Solution:

Understand what works for you, for this book, and realize that your voice is unique. That's good, that's what you want. Some folks won't like your voice. That's fine.

Chuck Wendig over at Terribleminds has a unique voice and it's not everybody's cup of tea. That's okay. He's doing fine, as will you.

You need to develop your voice and find your niche. And you aren't going to do any of that if you keep re-writing your stories until they sound like everyone else's!

3. You don't have to outline

Some folks are pantsers not plotters. If you're a pantser, that's fine. That's great!

Don't try and make yourself be something you're not.

Myself, I'm more of a plotter than a pantser, but sometimes I won't outline, especially with my shorter stories. If I feel something's missing, I can outline after I've written it and look at the structure to see if I have to add a scene, take something away, add a character, etc.

Problem:

When you outline your story you lose all interest. Writing is as interesting as watching paint dry.

Solution:

Don't outline! There's nothing wrong with outlining, but if it's not working for you try winging it.

Experiment.

Remember, each book is different. Don't think that just because you wrote the last book one way that you have to write your current book the exact same way.

4. Your story is a book, not an event.

In April, Kris Rusch wrote a terrific post called, Book as Event. If you haven't read it and want to publish your writing, I highly recommend it.

Kris Rusch writes:

Finishing the first novel had felt like a fluke. I managed to get it done and it felt daunting. The second novel felt less daunting, but much more important.Dean Wesley Smith writes:

Before I had believed that if I could do it once, then I could do it again. After I finished the second book, I knew I could do it again. And proceeded to do so more than a hundred times. (Believe me, that number freaks me out more than it freaks you out. Seriously.)

Finishing my first novel had been an event. A mountain climbed. A life goal achieved. It felt more important to finish than it did to publish the book. And the second novel, well, it felt even more important.

It did feel on par with giving birth to a wanted child.

Now, not so much. I’m still proud when I finish a novel, pleased at myself, pleased that something I imagined has become reality. But I also know there are more novels to write and more stories to tell and so much more to do. I’m actually more afraid of dying before I can finish writing all the projects I carry around in my head, and those projects increase exponentially as each year goes on. (See my Popcorn Kittens post. You’ll understand.)

Books sometimes are events and sometimes they aren’t. Before the rise of indie publishing, prolific writers understood this. (Book as Event)

"Books and stories are not events, they are just stories. Entertainment. Nothing more. But if you believe a book or a story is an event, it takes on a huge level of “Importance” to you and thus that book or story is almost impossible to let go of, or stop working on."Problem:

You're having a hard time moving onto your next book because you're discouraged by your previous books performance.

Solution:

Realize that a book isn't an event.

Write.

Write a lot.

As you write you'll get better and you'll develop a readership.

Dean goes on to talk about other points, but these four resonated with me, especially the first.

Dean ends by writing:

I sit alone in a room and make stuff up.You heard him, go have fun. Go write!

That’s my job description.

. . . .Readers now decide if they like my story or not, not some editor. And I can write as much or as little as I want without anyone yelling at me.

And I can make my books look exactly as I want them to look.

But most importantly, I can entertain myself.

I have thousands and thousands of choices now with my writing.

I have control and I have freedom.

And for me, all that is great fun.

Go have fun.

(Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations are from Dean's article, Having Fun.)

Photo credit: "Untitled" by Thomas Leuthard under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0.

Tuesday, July 23

15 Ways To Write A Story

Occasionally I come across an article on writing that's so good I have to share it. 15 Unconventional Story methods by Richard Thomas is one such article.

By "story methods" the author doesn't mean genre versus mainstream nor is he discussing the difference between stories of various lengths (though this is his 10th point). He is referring to the different forms a story can take. Doubtless, some of these you'll be familiar with--the epistolary form, for example--and some you might not--a story consisting of nothing but dialogue.

Let's dive in!

Different Forms A Story Can Take

1. Vignette

A vignette is not a complete story. Richard Thomas writes that it gives the reader "an image of a person, place, or idea" but there's no traditional plot, there's no conflict set up or resolved. This is not a story, it's a writing fragment.

When I was a kid I wrote a lot of these. Wonderful writing practice! Also, I could see something like this being used for effect as a part of a larger work.

2. Slice of Life

The slice of life story is more like a story than the vignette, but it still isn't a story as we traditionally think of it. For one thing it's generally incomplete and, as Richard Thomas writes, "focuses on the common, a random (or seemingly random) series of moments, scenes, and observations that do not always add up to a complete story—with resolution, and a set plot."

I've watched a number of art-house movies that have this feel. I've found that this form can be very effective in communicating a mood.

3. List

I haven't read many list stories, stories in which the events form a part of an ordered whole. For instance, Richard Thomas writes that:

"[T]ypically, it [a list story] is broken up into either numbered scenes, or a collection of objects or ideas under one concept. I’ve written a few list stories in my time. One of the first was “Twenty Reasons to Stay and One To Leave,” which had twenty-one total observations on a relationship that is doomed to end after a husband and wife lose a son. A lot of list stories have an actual number in the title, but it isn’t mandatory."

4. Epistolary

I've loved the epistolary form every since I read Dracula, a story told entirely through a series of letters/journal entries. But the form is versatile and has expanded to include emails, tweets, voice mail, and so on. Experiment!

5. All dialogue

This is just what the name suggests: a story written completely in dialogue. I've never read anything like this, but I want to! Richard Thomas writes:

"It’s very difficult to make this work, but it can be a lot of fun. How do you create setting? Well, they have to talk about it, right? It’s the same for your plot, conflict, and resolution."

6. Choose your own path

These can be fun when well done and, in any case, can lead to great discussions afterward. I heard that, years ago, someone was thinking of producing a movie where the audience voted on which ending they wanted to see. Of course it can be more fine-grained than that. Richard Thomas writes:

"You get to the end of a chapter and it gives you some options: If you want to open the door, go to page 12; If you want to stay and wait for the police, go to page 18; If you want to make a phone call, go to page 22."

7. Metafiction

Metafiction is wonderful when it's well done. This kind of writing "self-consciously and systematically draws attention to its status as an artifact in posing questions about the relationship between fiction and reality, usually using irony and self-reflection (Wikipedia, Metafiction).”

Richard Thomas points out that Stephen King's book Misery is a work of metafiction since it is "a story about a writer creating a story". Also, The Princess Bride--one of my all time favorites--is a work of metafiction because it is "a story about a reader reading a book".

Anything that breaks the fourth wall is metafiction.

I'll let you read the rest of the points over at litreactor.com. 15 Unconventional Story Methods is a wonderful article, especially if you're looking for an idea for your next story.

Happy writing!

Photo credit: "life's a beach" by Robert Couse-Baker under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0.

Saturday, July 20

What Writers Can Learn From Aaron Sorkin

Aaron Sorkin is a genius.

A while ago I blogged about an article he'd written that dissected the first few minutes of the opening scene of The Newsroom, explaining the effect he'd wanted to create in the viewer and what he did to create it.

Here is a clip of the opening scene of The Newsroom:

Here's Sorkin's article: How to Write an Aaron Sorkin Script, by Aaron Sorkin.

One of the reasons I'm posting about Aaron Sorkin's dissection of his own wizardry has to do with Stephen Pressfield's blog articles:

Art is Artifice, Part 1

Art is Artifice, Part 2

Stephen Pressfield writes:

In a nutshell:Great articles.

Real = unpublishable.

Artificial = publishable.

When I say “artificial,” I mean crafted with deliberate artistic intention so as to produce an emotional, moral, and aesthetic response in the reader.

What do I mean by “real?”

Real is your journal. Real are your letters (or these days your texts, tweets, Facebook postings.) Real is that which possesses no artistic distance.

Giving the artificial, giving one's art, a semblance of reality requires the kind of talent that only comes from many, many, hours of practice.

Here's an example of talent that comes from practise. This video (see below) was taken behind the scenes at the Tony Awards during the opening number. It's only 2 minutes long:

That director was using instinct. I'm sure that when he first started directing he had to think about it, but now he's like a musician carried away by the score or an athlete on a runners high.

Both Arron Sorkin and folks like the above director, folks who have worked in their chosen profession for decades, have put in the time.

They've worked, they've practiced, they've sacrificed, and now, at the pinnacle of their careers, they have these moments of unparalleled excellence.

Sorkin's opening scene was amazing, startling. Completely artificial and, possibly, absolutely true.

Artificial, because Sorkin crafted that scene: no one is that smart, that eloquent, that directed.

Completely true, because--through art--he extracted the underlying reality and presented it in a way that startled and entertained.

Did I mention that Aaron Sorkin in a genius?

My point in writing this long meandering post is that writing is supposed to be hard, it's supposed to take a lot of work, but you can do it.

Let me leave you with a video sent to me by a friend, it's a conversation Neil Gaiman had with Connie Willis at the World Fantasy Conference in 2011:

Photo credit: "Three trees" by Kevin Dooley under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0.

Friday, July 19

Stakes: 11 Ways To Make Readers Care

Chuck Wendig has written another fantastic article about writing, this time on the subject of stakes (NSFW -->): 25 Things To Know About Your Story’s Stakes.

Stakes: Making things matter

1. A story's stakes must be clear

The stakes must be clear. What will the protagonist lose if she fails to achieve her goal? What will she gain if she achieves it? Chuck Wendig writes:

"[W]hat is at stake? Life? Love? Money? A precious plot of land? The loyalty of an old friend? A wish? A curse? The whole world? Galaxy? Universe?"

2. Your protagonist's goal must be clear

Protagonists must want things. They can want more than one thing, but they must want one thing desperately and above all else. This thing that is desperately, passionately, wanted is the story goal. If the protagonist achieves the goal then they've succeeded, if they haven't then they've failed.

For instance, in Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark, if Indiana finds the ark and brings it back with him then he's succeeded. If not, he's failed.

What are the stakes? If Indie achieves his goal then he gets professional kudos and the opportunity to study a fascinating artifact. If he doesn't achieve his goal then the Nazi war machine will use the ark to help turn the tide of war in their favor.

Of course, the goal can change along the way. In The Firm Mitch McDeere starts out wanting to be a rich lawyer then, about halfway through the story, his goal changes: he just wants to be free. (He dosen't want either the FBI or the mob to own him.)

3. The stakes must matter to the characters

If the stakes don't matter to the characters ... well, that's like creating a beautiful car but neglecting to put any gas in the engine. If the stakes don't matter to the characters then there's nothing to drive the story.

Chuck Wendig puts it this way: "Why do they care? If they don’t give a damn, why will we?"

4. 'Pinning' the characters to the stakes: making the stakes matter.

A character's wants, needs and fears are what make the stakes matter.

One of my favorite scenes comes from The Princess Bride. I can't embed it, but here's a link to the (one minute, thirty second) video: Hello My Name Is Inigo Montoya.

Here, Inigo Montoya takes the life of the man (Count Tyrone Rugen) who killed his father in order to avoid paying him for the sword his father created. It is the story of the injustice done to Inigo's father, Inigo's deep love of his father, his thirst for revenge, his fear that his years of sword training to best the six fingered man will have been in vain ... it is all those things, the messy human stuff, that makes the character--and us!--care about the six fingered man's death, that makes us (okay, me) glory in it.

5. Create conflicts of interest

Chuck Wendig's post is about stakes, but we can't talk about stakes without talking about goals. A story gains depth and texture when the goals of at least two characters are mutually exclusive. The goals of the protagonist and antagonist, for example.

In The Princess Bride this was, I thought, especially well done. In the beginning Inigo Montoya's goal--to kill the man in black (/Westley)--conflicts with Westley's goal to save his one true love. Then, later, Inigo and Westley join forces against Count Rugen and Prince Humperdinck, respectively.

In the end, these shifting alliances give the story a depth, an interest, it would otherwise lack.

As Chuck Wendig writes:

"Every character won’t necessarily gain and lose the same things in a story. What’s fascinating is when you pit the stakes of one character against the stakes of another (and one might argue this is exactly what creates the relationship between a protagonist and an antagonist). A gain for one is a loss for the other."

6. Stakes: Internal and External

Back to goals.

Characters have internal and external goals.

For instance, in Shrek the protagonist's internal challenge/conflict was to risk rejection and let people in, to risk rejection and let others know how he really felt (tell Fiona he loved her) so he could make connections, make friends (with Donkey), and find true love.

Shrek's outer challenge was to rescue Princess Fiona so Lord Farquaad would get all the creatures of fairy out of his swamp.

Different kinds of stakes accompany the different kinds of goals. If Shrek failed to get the creatures out of the swamp, Lord Farquaad would have had Shrek killed. If Shrek failed to lower his defenses and let people in, he would have lost the love of the Princess Fiona and had a sad and lonely existence in his now vacant swamp. A pyrrhic victory.

7. It's not size, it's complexity

It's not the size of the stakes that count, it's their complexity. Chuck Wendig writes:

"It’s all well and good to have some manner of super-mega-uh-oh world-ending stakes on the line — “THE ALPACAPOCALYPSE IS UPON US, AND IF WE DON’T ACT LIKE HEROES WE’LL ALL BE DEAD AND BURIED UNDER THE ALPACA’S BLEATING REIGN” — but stakes mean more to us as the audience when the stakes mean more to the character. It’s not just about offering a mix of personal and impersonal stakes — it’s about braiding the personal stakes into the impersonal ones. The Alpacapocalypse matters because the protagonist’s own daughter is at the heart of the Alpaca Invasion Staging Ground and he must descend into the Deadly Alpaca Urban Zone to rescue her. He’s dealing with the larger conflict in order to address his own personal stakes."

8. Escalate the stakes

Often a protagonist/hero will start off a quest to get something they want, something that will make their life better. Then they find out that it they don't get it--this thing, whatever it is--not only will their life not be made better (they won't win the million dollars and be able to quit their crappy 9 to 5 job) but it will be made much worse (they'll lose their home and their grandma will have to stay in a nightmare of a retirement community).

By the end of the story they'd be happy just to get back what they had at the beginning and go to their 9 to 5 job and thank their lucky stars they had food to eat, a place to sleep and people to hang out with. Why? Because by the end of the story their world has been turned upside down and it's impossible for things to go back to the way they were.

Generally there's a setback for the hero at the end, a big setback.

This setback could be anything, but let's say it looks as though our protagonist/hero has lost. She's failed to achieve her goal. Not only that, but the stakes--what happens if she does/doesn't achieve her goal--are heightened. Now, not only will our protagonist lose her job and her home, but so will everyone who has helped her on this quest. This, in turn, causes everyone (well, everyone except her mentor who just died a horrible death for standing up to the evil bully) to desert her.

I'm not saying this happens in every story--it doesn't--but the stakes, whatever they are, will escalate. That's part of how one creates dramatic tension/narrative drive.

9. Escalate, complicate, or both

Chuck Wendig writes:

"We can escalate stakes by complicating them and we have at our disposal many ways to cruelly complicate those stakes. A character can complicate the stakes by making bad choices or by making choices with unexpected outcomes (“Yes, you killed the Evil Lord Thrang, but now there’s a power vacuum in the Court of Supervillains that threatens to destroy the Eastern Seaboard you foolish jackanape.”) Or you can complicate the stakes by forcing stakes to oppose one another — if Captain Shinypants saves his true love, he’ll be sacrificing New York City. But if he saves the millions of New York City, he’ll lose the love of his life, Jacinda Shimmyfeather. Competing complicated stakes for characters to make competing complicated choices."

10. Story stakes and scene stakes

Stakes come in different sizes.

You have big stakes--story goal sized stakes--but you can have smaller, micro-sized, scene sized, stakes as well.

For instance, in Indiana Jones and the Lost Ark, there's a terrific scene in the middle where Indie ducks into a tent to hide from the bad guys and comes across Marion tied up. Indiana is dressed in native garb so, at first Marion doesn't recognize him. Indie (who thought she was dead) begins to untie her then realizes that if the Nazis discover Marion missing they'll know Indie is there looking for the ark. He can't give himself away.

So, what does Indie do? Well, he ties her back up, of course! Marion is furious with him, naturally. It's a great scene.

Lets take a look at the stakes at play. At the beginning of the scene Indie is trying to hide from the guard because he wants the ark.

Indiana's stakes:

Goal: Escape the guards notice and obtain the ark.

- Success: Indiana doesn't get captured and is one step closer to his goal.

- Failure: Indiana is captured, possibly tortured. He fails to obtain the ark and the world is taken over by Nazis.

Marion's stakes:

Goal: Get untied, sneak out of the camp, go to America.

- Success: Freedom.

- Failure: The unknown. She could be tortured, various nasty things could happen to her.

In the middle of the scene the stakes change when Indie realizes he has to tie Marion back up or risk losing the ark.

Indie's goal: To not completely alienate the affections of Miriam.

- Success: Marion's love and gratitude.

- Failure: Her lasting wrath.

For Indie to succeed in winning Marion's affection--or just to avoid making her furious with him--he must help her escape. But he can't. If he does then he risks his primary mission. So he accepts Marion's wrath, ties her back up, and exits the tent.

The point is that mini-goals with their own stakes can pop up within a scene. The scene between Indiana and Marion was especially interesting, I thought, because it highlighted their diametrically opposed interests. Marion would much rather just escape and forget all about the ark, but not Indie.

Chuck Wendig writes:

"Stakes smaller than those able to prop up subplots — let’s call ‘em “micro-stakes” — can instead be used to support a scene. When entering a scene, you should ask: “What are the stakes here?” The characters in any given scene are here in the scene consciously or unconsciously trying to create a particular outcome for themselves or for the world around them. Something is on the table to be won or lost... The stakes needn’t be resolved by the end of the scene, and may carry forward to other scenes..."

11. Stakes in dialogue

I hadn't thought about it like this before I read Chuck Wendig's article, but dialogue has goals with stakes attached, or at least it probably should. After all, we communicate for reasons, because we want things. He writes:

"Dialogue in a story is purposeful: it’s conversation held captive and put on display for a reason. Dialogue in this way is frequently like a game, a kind of verbal sparring match between two or more participants. Again: things to lose, things to gain. Someone wants information. Or to psyche someone out. Or to convey a threat. Purpose. Intent. Conflict. Goals."

# # #

Altogether a fantastic article on writing, another in a long line. I'd encourage you to head on over to Chuck Wendig's site and read it for yourself: 25 Things To Know About Your Story’s Stakes.

An Apology

I intended to post this blog yesterday, but, instead, had to move brown cardboard boxes filled with memories.

I'm undergoing that horror known as 'moving'.

Sounds innocuous, doesn't it? But it means I'm neither here nor there. I live at two addresses--the old and the new--but, really, I'm at home at neither because my life has been parceled up into crates and stacked along walls.

As I creep through unfamiliar hallways staring at the brown corrugated reminders of work to come, the boxes begin to seem vaguely challenging. Perhaps threatening.

I think I need to read a Stephen King novel and write a horror story about moving!

Thanks for being patient with me. :)

Cheers, and good writing.

Photo credit: "Flying Ninja Man" by Zach Dischner under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)