What makes a character memorable?

Deborah Chester writes in her article, Bonding with Your Characters:

"We want readers to either love or hate our characters. What we don’t want is a 'meh' reaction. Or even worse, 'Who? I don’t remember her.'"

The question: What qualities do vivid, well crafted, memorable characters have?

1. Memorable characters are exceptional. Novel.

I want my readers to obsessively worry about my protagonist and loathe my antagonist. This only happens if I’ve managed to craft memorable characters, and exceptional traits are memorable.

We don’t fall in love with characters who are boring and forgettable. Think about Captain Hook in Peter Pan. The man is deathly scared of a crocodile who has eaten his hand, has a ticking clock in its belly and now views Captain Hook as a nice tasty snack. Or take Peter Pan, he is perennially young and has a feisty fairy--one with a mad crush on him--for a best friend.

What makes something memorable?

You could notice many things about your environment, so many things it would be impossible to take them all in at once. So, what do you remember? Of course it’s the thing that sticks out, the thing that doesn’t fit in, the thing that is conspicuously different from everything else.

Lukewarm, middle-of-the-way characters, don’t stand out and so aren't memorable. (BTW Jim Butcher, author of The Dresden Files and creator of the very memorable Harry Dresden, has a really good blog post on this, I urge you to read it: Characters.)

One of my favorite books is William Goldman's novel The Princess Bride. I love, or love to hate, every single character in that story. And I’m sure I’m not alone, If you've never read William Goldman's masterpiece, please, please, do.

2. Characters need clear motivation.

A character's motivation and her goal are intimately related yet distinct.

Let’s break this down. What is motivation?

Motivation is a particular state of affairs that impels a character to pursue another state of affairs, one that represents the character’s goal.

For example: Susie is in a boat frantically rowing toward a sandy shore. Why? What is her motivation? Susie is being chased by a huge shark with long white serrated teeth. Where is she going? What is her goal? Susie is heading toward the safety of the beach.

In this example, the danger the shark embodies provides Susie her motivation for rowing and the safety of the beach is her goal. Yes, one could say that her goal is to escape the shark--and that would be true--but I think it helps to keep the states of affairs separate.

3. If a character has a strength, something she excels at, she will be more memorable.

Before we talk about the importance of skills and excelling, let’s talk about the importance of the antagonist being stronger than the protagonist.

3a. The antagonist should be stronger than the protagonist

Jim Butcher was the first person to make me realize that the antagonist needs to be a bit stronger than the protagonist. Why? Because throughout most of the story the antagonist needs to best the protagonist. Also, the struggle between protagonist and antagonist needs to be real and challenging and it’s not going to be if the protagonist is stronger; then we would expect him to win. If there isn’t a more powerful force pushing against the protagonist, motivating the changes he makes to his life, then the stakes introduced won’t make sense and the story isn’t going to be interesting.

Jim Butcher writes:

"Your villain has to have enough power, of whatever nature, at his disposal to make him a credible threat to your hero. Personally, I believe that the more the villain outclasses the hero, the better. David wouldn’t have gotten nearly the press he did if Goliath had been 5’9” and asthmatic."

Jim Butcher, author of the fantastically entertaining series The Dresden Files, has written a series of blog posts in which he gives extremely good, eminently readable writing advice. His posts are terrific, so much so that I’ve assembled an index for them here: Jim Butcher on Writing.

3b. The protagonist needs a unique skill that he becomes really good at toward the end of the story.

You might be wondering, “Well, if the antagonist is stronger than the protagonist, how could he beat him?” By changing, by growing, by learning when the antagonist doesn’t or can’t.[1] Also--and this is terribly important--the protagonist needs a skill, something that he does better than anyone else, and he needs to develop this skill throughout the story.

Think of Luke Skywalker in Star Wars IV: A New Hope. Luke has a skill, something unique to him: He has the capacity to use The Force.

If the protagonist beats the antagonist at the end of the story this victory needs to be earned. (And, by the way, the protagonist doesn’t need to beat the antagonist, he can also lose, but those stories don't seem to be as popular! People like to have hope that tomorrow can be better than today.)

In order to earn their victory the protagonist has to be great at something, something that only he can do. In practise this means that the protagonist needs to have some characteristic, some trait, that will, in the context of the specific environment of the confrontation, allow the protagonist to plausibly beat the antagonist.

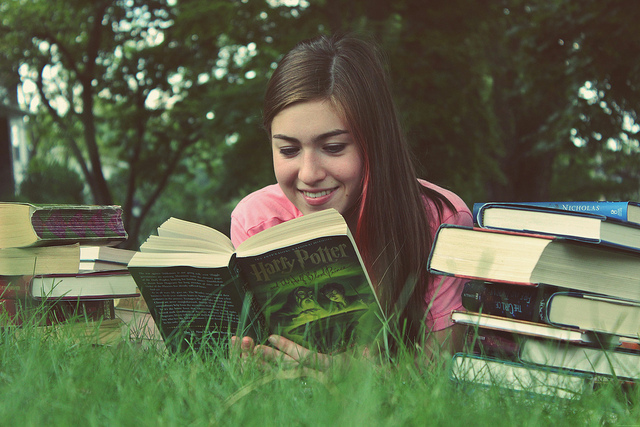

Yesterday I re-watched Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. It was a lovely movie. If you’ve seen it, recall that Harry defeated Voldemort because of a special property related to his touch. His touch was deadly to Voldemort because Harry was still protected by his mother’s spell, the spell that resided in his blood.

Or, think of a mystery story, one of Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot adventures. Poirot could solve mysteries that flummoxed everyone else because he used his ‘little grey cells’ and paid attention to the psychology of the situation. Mr. Monk, another wonderfully quirky detective, was aided by his obsessive and involuntary attention to detail. As Monk often said, “It’s a gift and a curse.”

4. Characters need weaknesses and flaws.

As I have said, a story is about change. It is about a character who wants something so desperately that he is willing to change who he is so that he can overcome a specific obstacle to achieve his goal.

But, none of this change would be possible if the protagonist didn’t start out with a weakness. So let’s talk about the importance of flaws.

Major Flaws

Generally, a major flaw is a beefy, serious thing that prevents a character from achieving his goal. This could be a mental illness such as Mr. Monk's obsessive compulsive disorder or what might be seen as a physical weakness like Dr. Watson had in the first episode of Sherlock (his psychosomatic war injury).

Classic examples: some sort of physical malady such as the loss of a sense (sight, hearing, etc.), loss of memory, or a character flaw such as greed, lust, wrath, pride, and so on. Arguably, Walter White's weakness was his pride. Frodo's weakness wasn't a character flaw, it was the One Ring he carried that made him vulnerable to the siren call of the dark side.

Minor Flaws

Minor flaws are minor because they don't affect the main storyline in any significant way and are often played for comedic effect. Indiana Jones was scared of snakes. Jack Ryan was afraid of flying.

5. Exceptional characters are unique.

As I have said, each character in your story should be memorable and part of this is being unique. One way to achieve this quickly is to give each character tags and traits. I'll talk about this more in a later post.

That’s it! In my next post I’ll talk about a practical way to make characters memorable by discussing character tags.

Notes:

1. Strictly speaking, this isn’t true. In some stories the antagonist also grows and changes. For example, this often occurs in romance stories. Say there’s a female protagonist and male antagonist and these two characters begin the story hating each other but end it in a loving committed relationship. Here both the protagonist and antagonist will have changed and grown. These stories can be a wee bit tricky because the changes usually need to be complementary so that, in the end, the main characters grow together rather than apart.

Other posts in this extended series (I'm blogging a book):

How to Write a Genre Story: The Index