I loved

The Dead Zone by Stephen King. I read the novel, watched the movie and then, much later, the TV series starring Anthony Michael Hall.

What's that advice writers are always given? We are urged to read the best, read what works. I shared a quotation of Stephen King's yesterday and one part of it stayed with me. King wrote that

[R]eading offers you a constantly growing knowledge of what has been done and what hasn't, what is trite and what is fresh, what works and what just lies there dying (or dead) on the page. (Stephen King, On Writing)

As I mentioned the other day in my post (

The Magic Of Stephen King: How To Write Compelling Characters & Great Openings) the hallmark of Stephen King's writing (for myself) was its ability to (metaphorically) grab me by the throat in the first few paragraphs and drag me, at times kicking and screaming, through the novel.

I say 'kicking and screaming' (this is along the lines of the confession of a deep, dark, secret) because I don't like horror! Well, no, that's not true. What I don't like is a certain

kind of horror, the nails on a chalk-board kind of psychological horror that Stephen King so masterfully produced in, for example,

Misery.

I loved

Misery. I read it cover to cover in a couple of days and then never read another King book for

years. I was too scared!

Think about that. Stephen King got me to identify with John Smith so strongly I spent upwards of 8 hours of my life reading something that genuinely horrified me, and not in a good way. That, ladies and gentleman, is character identification on steroids. (Stephen King is also a master at generating narrative drive. See:

Writing: The Starburst Method, Part 8: The Rough Draft & Narrative Drive)

So now to the question: How does Stephen King do it?

An Analysis Of Stephen King's The Dead Zone

I know I've been talking about

Misery, and I will get to that analysis one day soon, but today I'm going to discuss

The Dead Zone.

The question: How does Stephen King do it? How does he create that kind of Krazy Glue-like attraction, that bond, between the reader and his creations? His characters?

A few days ago I analyzed King's book,

It, and, in that post, mentioned Michael Hauge's 5 ways to create character identification and attempted to use Michael's categories to analyze how King was able to weave his magic. If you're unfamiliar with Michael's 5 ways or what I mean by character identification, you might want to take another peek at it:

How To Get Your Readers To Identify With Your Main Character.

The text: the first three paragraphs of The Dead Zone

By the time he graduated from college, John Smith had forgotten all about the bad fall he took on the ice that January day in 1953. In fact, he would have been hard put to remember it by the time he graduated from grammar school. And his mother and father never knew about the fall at all.

They were skating on a cleared patch of Runaround Pond in Durham. The bigger boys were playing hockey with old taped sticks and using a couple of potato baskets for goals. The little kids were just farting around the way little kids have done since time immemorial--their ankles bowing comically in and out, their breath puffing in the frosty twenty-degree air. At one corner of the cleared ice two rubber tires burned sootily, and a few parents sat nearby, watching their children. The age of the snowmobile was still distant and winter fun still consisted of exercising your body rather than a gasoline engine.

Johnny had walked down from his house, just over the Pownal line, with his skates hung over his shoulder. At six, he was a pretty fair skater. Not good enough to join in the big kids' hockey games yet, but able to skate rings around most of the other first graders, who were always pinwheeling their arms for balance or sprawling on their butts.

I usually don't use extensive quotations but since we're examining Stephen King's writing it helps to have the text before us.

First paragraph

In the first paragraph Stephen King starts introducing what I'm going to call "The Threat". I'll talk more about this in another post, but I'm fairly sure that some version of The Threat appears in most of his stories. In

The Dead Zone we learn of a 'bad fall'. That we're hearing about this in the first paragraph and that King spends the entire paragraph on it tells us this is something important.

So what is paragraph two about? That's right! The fall.

Stephen King doesn't tell us in the first paragraph that the fall is a terrible thing but, well, it's a

bad fall and, besides, when are falls ever a

good thing? King does a lot of work in this first paragraph. We hear about The Threat right away, first thing, and we know who The Threat endangers: John Smith.

Second paragraph

Another thing I've found in most of Stephen King's stories is

vulnerability. There is a threat and he introduces us to characters who are

vulnerable. In

It the paper boat was vulnerable to the water it sailed on just as the little child was vulnerable to the conditions the storm left in its wake.

In the second paragraph of TDZ King starts to build up our picture of the child John Smith once was by telling us about his world. Look at his language:

- bigger boys

- little kids

- old taped sticks

- potato baskets for goals

- their [the little kids] ankles bowing comically in and out

The language is nostalgic. "Remember when we were kids?" he is saying. Even myself--I never skated on pond ice and rarely skated in a rink and never, ever, took part in a game of hockey--I can picture this. I wish I

had been there.

King's language is vivid. Evocative. I've seen the scene he's painting/creating. It's true that I never did any of those things but I'd seen kids out on the ice, even wished I was one of them. So I guess one reason it's easy for me to identify with this nostalgic vision of yesteryear is that I'd like this to be true/real. I'd have liked

my childhood to have been like this.

Third paragraph

Now we're tying things together. The first thing I'd like you to notice is the first word of this sentence. Stephen King is no longer talking/writing about "John Smith" he's writing about "Johnny".

Also notice there has been a considerable amount of movement. The first paragraph--the feeling, the mood--was detached. Almost distant. Then we got all sticky and nostalgic about 'the way it was' and now SK is showing us the protagonist again, but we're not seeing John Smith, we're seeing

Johnny. We're seeing the protagonist when he was an innocent child before anything bad happened to him, the child living in this lovely nostalgic world.

The second and third paragraphs show the child, and the child's world, before The Fall. (Now that I've written the words, I realize again how powerful imagery can be.)

- Johnny is a "pretty fair skater". He's "able to skate rings around most of the other first graders."

Recall that one of Michael Hauge's 5 points was to make your character good at something. And not just anything, something--a skill--that is valued in the character's world. If your character is a football player and he's great at chess it's not going to help!

Also, notice that Stephen King maintains--perhaps even steps up--building his evocative, nostalgic, image of childhood. King writes that the other first graders "were always pinwheeling their arms for balance or sprawling on their butts". Now THAT I remember! I remember ice rinks and being bundled up in layers of winter clothes until I looked like the original

Michelin Man--and I had about the same mobility! At least the falls didn't hurt as much.

What Does This All Mean?

I'd like to stress that what I've done here, the analysis I've made of Stephen King's work, isn't meant to be in any way authoritative. If you agree with something I've said and you think it may make your writing stronger then that's wonderful! Use it. But if you don't, or if you see something completely different, then go with that.

I do think reading great writing, writing that moves you, and then attempting to analyze what it was about the writing that created that effect in yourself, can help a writer become better at her craft. Perhaps in the final analysis it's the

only thing that can.

But everyone, every single person, is different. What I find emotionally compelling might not seem so to you, what turns me into the proverbial puddle of tears may leave you cold.

That's why it's important for each of us to read what works

for us, as well as what doesn't, and then examine each story to see

why the one gripped us emotionally and the other didn't.

# # #

Who is your favorite writer? What is it about their prose that hooks you? That produces that can't-put-it-down quality which drags you, willing or not, through the book?

Other articles you might like:

-

The Magic Of Stephen King: How To Write Compelling Characters & Great Openings

-

How To Sell Books Without Using Amazon KDP Select

-

Edward Robinson And How To Sell Books Using Amazon KDP Select

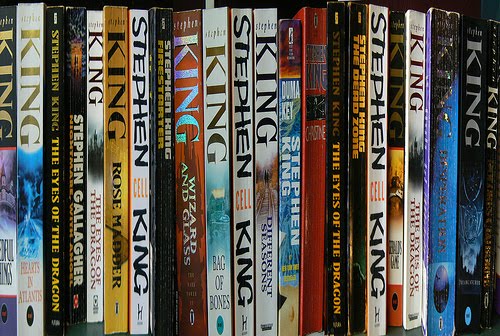

Photo credit: "

Stephen King" by

robbophotos under

Creative Commons Attribution 2.0.