How To Write A Bestseller

If anyone knows, please do tell! Of course part of it is luck. Getting your content out in front of the right people at the right time.

Topic counts too. Writing about something--whether it be hobbits in Middle Earth, buried silos, or kids finding a body--that will grab the public's attention, something they will be intrigued by enough to both read and recommend.

So, other than that, what's the secret to writing a bestseller?

Of course I know there's no secret, not really, but I do think there may be rules of thumb.

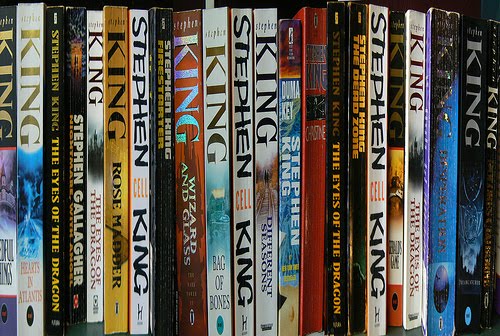

When I read Stephen King's work--and I know I keep mentioning Mr. King--but he has had an enormously successful career and his work has been used as an example of how to write in many of the writing workshops I've taken as well as in many of the books on writing I've read.

Dig Deep And Go For The Emotional Jugular

When I read Stephen King's work what has struck me is this: the emotional connection.

Always, always, always I feel for the characters, there is a part of me that emotionally connects with them, their successes and their failings. It's not a thinking thing, this connection, it's an emotional thing. It's not a matter of the head but of the heart.

Right now I'm reading Dean Koontz's novella, What The Night Knows. His opening paragraphs paint a picture. It's a beautiful, compelling opening that does a good job of both drawing me into the story and creating an atmosphere, a feeling.

But it's a different feeling from that created by King. It is more about thinking and looking, about understanding the characters. I like the characters, I'm interested, I do care about them, but I'm not emotionally invested in them they way I get when I read a King novel. I feel protective of those characters the way I feel about my good friends.

Of course, I'm talking about my responses. You may have had different responses. In which case, I'd love to hear from you in the comments!

An Analysis Of Stephen King's Misery

I will talk about Misery but first I'd like to backtrack a bit.

I've previously written about It and The Dead Zone, two of my favorite books by Stephen King (It is one of my favorite books by any author). Another book King wrote, and that sold well, and that was said to be, by some, one of his best books, was Misery.

Misery begins differently than many of Stephen King's other books, with a man struggling to regain consciousness. But, in each case (The Dead Zone, It, Misery) there is a dilemma, almost a contest, that starts things off. Always, this dilemma/contest is intensely personal for the main character.

The Dead Zone

In The Dead Zone Johnny, a six year old boy, goes down to the local pond to ice skate. He's good at ice skating, better even than the other kids his age. The contest is between Johnny and the other children as well as between Johnny and himself.

Specifically, Johnny wants to do something he's never done before, something Timmy Benedix could do: Skate backward. King writes:

[Johnny] skated slowly around the outer edge of the clear patch, wishing he could go backward like Timmy Benedix, listening to the ice thud and crackle mysteriously under the snow cover farther out ... He was very glad to be alive on that cold, fair winter day. Nothing was wrong with him, nothing troubled his mind, he wanted nothing ... except to be able to skate backward, like Timmy Benedix.Just then, in the midst of his six-year-old elation he receives the injury that will change the rest of his life.

. . . ."Timmy!" he shouted. "Watch this!"

He turned around and began to skate clumsily backward. Without realizing it, he was skating into the area of the hockey game.

. . . .[H]e was doing it! He was skating backward! He had caught the rhythm--all at once. It was in a kind of sway of the legs ...

The Dead Zone: Analysis

So, what do we have? A sympathetic character achieves a personal goal, does something, accomplishes something, that gives him a great deal of satisfaction and that readers can relate to (a lot of kids have strapped on ice skates and done a few laps around an ice rink).

Then the sympathetic character, through no fault of their own, receives a crushing blow that will transform the rest of their life. As a result of this blow they have a challenge: Give in or overcome.

Stephen King's It

The Dead Zone was published in 1979 while It wasn't released until 1986 (Stephen King Biography). But, still, these books open in remarkably similar ways.

At the beginning of It we meet George who is, like Johnny, age six. George is "a small boy in a yellow slicker and red galoshes" who runs along beside a boat made out of newspaper.

George is adorable.

The boat was made by his brother, Bill. Bill loves George and would have played with him but he was ill and confined to bed.

This is the 'through no fault of his own' part. Bill couldn't help being sick and not being able to help his brother. Yes, he made the newspaper boat for his brother, and yes George probably wouldn't have died that day, that way, if he hadn't been playing with the toy Bill made for him. But still it wasn't Bill's fault. Though, of course, we understand that Bill wouldn't feel that way about it.

When the newspaper boat goes off the side of a "deep ravine" George laughs aloud, "the sound of solitary, childish glee a bright runner in that gray afternoon".

George's "strange death" is the crushing blow life delivers to Bill the way falling on the ice, the injury he received, was Johnny's.

Openings

What I've talked about so far are openings, just openings, and that's all I'm going to do because, really, those first few paragraphs are the most important determiners of whether your book will sell, whether the person reading your work will buy it.

The rest of the book sells your next book, or perhaps one from your backlist. It's the first few paragraphs that sells the one a potential fan, a potential buyer, opens up and starts to read.

At least that's how I look at it.

Stephen King's Misery

So, let's look at Misery now. What's the setup here?

A man, Paul Sheldon, gets into a car accident while driving under the influence. He is rescued by Annie Wilkes and nursed back to life in her spare bedroom.

For the first few paragraphs Paul is fighting for consciousness. Here's King's first mention of Annie Wilkes:

His first really clear memory of this now, the now outside the storm-haze, was of stopping, of being suddenly aware he just couldn't pull another breath, and that was all right, that was good, that was in fact just peachy-keen; he could take a certain level of pain but enough was enough and he was glad to be getting out of the game.There's a lot to say about that passage. Yesterday I wrote about Ray Bradbury and mentioned what he had said in Zen In The Art Of Writing about it being important for writers to read poetry. I'd wager that Stephen King reads his fair share of poetry! It's a beautiful example of poetic prose.

Then there was a mouth clamped over his, a mouth which was unmistakably a woman's mouth in spite of its hard spitless lips, and the wind from this woman's mouth blew into his own mouth and down his throat, puffing his lungs, and when the lips were pulled back he smelled his warder for the first time, smelled her on the outrush of the breath she had forced into him the way a man might force a part of himself into an unwilling woman, a dreadful mixed stench of vanilla cookies and chocolate ice cream and chicken gravy and peanut-butter fudge.

He heard a voice screaming, "Breathe, goddammit! Breathe, Paul!"

The lips clamped down again. The breath blew down his throat again. Blew down it like the dank suck of wind which follows a fast subway train, pulling sheets of newspaper and candy-wrappers after it ...

Anyway, that's not what we're discussing right now!

This passage seems to follow the previous pattern, though not as obviously. No, we don't have a six year old child, but we do have someone vulnerable. Helpless. Sympathetic.

The crushing blow is Annie Wilkes; Paul's car accident and being rescued by her--if one can call it a rescue!

The rest of Misery is about how Paul deals with the crushing blow. Does he let his situation get the better of him or does he fight like hell and overcome?

That, I think, is a common setup for King's books.

The Pattern

I'm not saying that Stephen King has a formula, not at all. I'm just saying I've noticed a certain pattern to a few of Mr. King's openings and the pattern goes something like this:

A sympathetic character under stress (they have either achieved something or had something important stripped away from them) receives a crushing blow that will transform the rest of their life. As a result of this blow they have a challenge: Give in or overcome.This is the last installment of my series, The Magic Of Stephen King, but I want to write other articles that look at what makes certain stories--fictional or otherwise--work. What makes certain videos, certain news stories, go viral? What makes certain books bestsellers? But that's for another day!

What other stories--they could be Stephen King's but they don't have to be--fit this pattern? Have you written a story that fits this pattern?

Other articles you might like:

- Ray Bradbury On How To Keep And Feed A Muse- Fleshing Out Your Protagonist: Creating An Awesome Character

- Dean Koontz And 5 Things Every Genre Story Needs

Photo credit: "Another day in paradise" by CptHUN under Creative Commons Copyright 2.0.