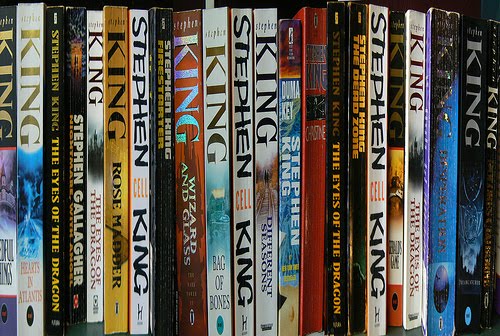

Today I continue my previous discussion of Stephen King’s book, On Writing. (see: The 5 Best Books on Writing)

At the end of my last post I promised I would talk about Stephen King’s best advice for writers. Let’s do this as a countdown. Starting us off, here’s number five:

At the end of my last post I promised I would talk about Stephen King’s best advice for writers. Let’s do this as a countdown. Starting us off, here’s number five:

5. Fear Is The Muse-Killer

“I’m convinced that fear is at the root of most bad writing. If one is writing for one’s own pleasure, that fear may be mild.... If, however, one is working under deadline … that fear may be intense.”

“Good writing is often about letting go of fear and affectation. Affectation itself, beginning with the need to define some sorts of writing as “good” and other sorts as “bad,” is fearful behavior.”

4. The Magic Is In You

“I’m often asked if I think the beginning writer of fiction can benefit from writing classes or seminars. The people who ask are, all too often, looking for a magic bullet or a secret ingredient or possibly Dumbo’s magic feather, none of which can be found in classrooms or at writing retreats, no matter how enticing the brochures may be.” King uses Dumbo’s magic feather also as an analogy for the illusory appeal of adverbs (and quick fixes of all kinds) and a writer’s desperate clutching at them. At the base of this clutching is—as we’ve just seen—fear. Stephen King admonishes us to remember that Dumbo didn’t need the feather to fly. And neither do we.3. Have An Ideal Reader (I.R.)

“When I write a scene that strikes me as funny (like the pie-eating contest in “The Body” or the execution rehearsal in The Green Mile), I am also imagining my I.R. finding it funny. I love it when Tabby [King's ideal reader] laughs out of control—she puts her hands up as if to say I surrender and these big tears go rolling down her cheeks. I love it, that’s all, fucking adore it, and when I get hold of something with that potential, I twist it as hard as I can. During the actual writing of such a scene (door closed), the thought of making her laugh—or cry—is in the back of my mind. During the rewrite (door open), the question—is it funny enough yet? scary enough?—is right up front. I try to watch her when she gets to a particular scene, hoping for at least a smile or—jackpot, baby!—that big belly-laugh with the hands up, waving in the air.” When you write your first draft, write it for yourself. But stories are meant to be told. They are crafted with an audience in mind, even an audience of one. On the first draft—door closed to the world—write for yourself, write imagining your ideal reader. Would he/she laugh? Cry? Be bored? Scared? Irritated? When you rewrite you are no longer writing just for yourself and your ideal reader, now you are writing for the world (door open). Now you want to do two things. First, remove everything that doesn’t serve the story and, second, twist it as hard as you can. If you’re going for a laugh, make it the biggest laugh you can. If you want to scare your reader, terrify them.2. Writing Is Seduction

“Language,” King writes, “does not always have to wear a tie and lace-up shoes. The object of fiction isn’t grammatical correctness but to make the reader welcome and then tell a story …, [it is] to make him/her forget, whenever possible, that he/she is reading a story at all.” Yes! That. Of course King doesn’t mean that anything goes. He explains: “It is possible to overuse the well-turned fragment … but frags can also work beautifully to streamline narration, create clear images, and create tension as well as to vary the prose-line. A series of grammatically proper sentences can stiffen that line, make it less pliable. Purists hate to hear that and will deny it to their dying breath, but it’s true. … The single-sentence paragraph more closely resembles talk than writing, and that’s good. Writing is seduction. Good talk is part of seduction.” Okay, we’ve reached it! Stephen King’s best advice for writers:1. Write To Make Yourself Happy

Stephen King writes not because it makes him millions of dollars—I’m sure he would continue to write even if he flipped burgers for a living. He writes because it makes him happy. “Writing isn’t about making money, getting famous, getting dates, getting laid, or making friends. In the end, it’s about enriching the lives of those who will read your work, and enriching your own life, as well. It’s about getting up, getting well, and getting over. Getting happy, okay? Getting happy. Some of this book—perhaps too much—has been about how I learned to do it. Much of it has been about how you can do it better. The rest of it—and perhaps the best of it—is a permission slip: you can, you should, and if you’re brave enough to start, you will. Writing is magic, as much the water of life as any other creative art. The water is free. So drink.” If you haven’t read Stephen King’s, On Writing, I would encourage you to. If I could point to any one thing that made me a better writer, it would be King’s advice in this book. In the end, that’s all we can shoot for, not to be as good as the writers we admire, but simply to be better than we are.Other articles you might like:

The Magic Of Stephen King: How To Write Compelling Characters & Great OpeningsStephen King: How His Novel "Carrie" Changed His Life

My Analysis of 16 books: Stephen King is correct, the adverb is not your friend.