I’ve been mulling over a pattern I’ve noticed: my work that has received the highest praise from readers is work in which I wrote about, if I may put it like this, the peculiar themes of my life. My hopes and fears, my hangups and triggers. My deep, dark, secrets.

Of course I didn’t just slap my traumas on the page and say: Here you go! No, I transformed them into the language of the story.

For example (and my apologies if I’ve mentioned this scene previously), in one of my scenes I had my protagonist sit down to coffee with her overbearing mother. To say that they didn’t get along is an understatement of staggering proportions. It’s like calling the Hindenburg disaster “unfortunate.” But the protagonist needed a favor, so she was trying to make nice.

Well, as they sipped their coffees and chatted my protagonist came to an uncomfortable realization. She saw her mother not just as a parent but as a person, as a more-or-less ordinary human being. More than that, she realized her mother was suffering, that in fact she had been suffering for a while. She was being crushed by the weight of carrying, of safeguarding, her many secrets. Over the years these secrets had eaten away at the woman, at her sanity. My protagonist feels guilty and tries, in her stumbling inelegant way, to let her mother know she loved her and she didn’t need to be alone.

When I wrote this scene my own mother was in the hospital, slowly slipping away. In that scene ... I suppose it was a way for me to say things to my own mother that, due to her condition, she was beyond hearing.

Sorry for the melancholy post! My point is that readers were able to relate to my protagonist in that scene in a way that transcended the specific story I was telling and which, ultimately, helped bring it to life.

In connecting with my emotions concerning my mother, in channelling them into the scene, I made it better. Why? Because it brought to bear my specific experience of this universal human experience.

A Word of Warning

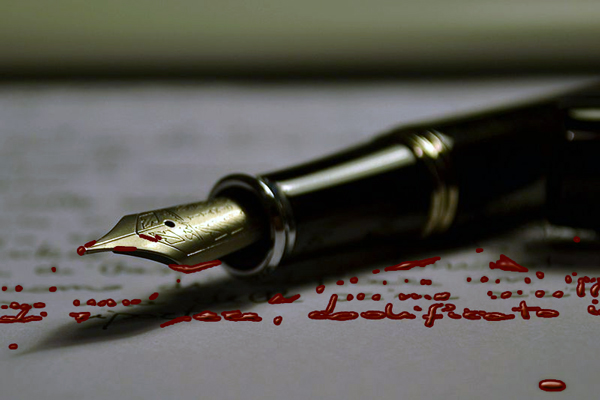

No doubt you’ve all heard the expression, often attributed to Ernest Hemingway, “Writing is easy. You just open a vein and bleed.”

The first time I read this quotation it resonated with me, but I didn’t realize that what I’ve been talking about – translating both the happiest and most painful experiences in life into one’s work – is how we bleed.

At least, that’s my take on it.

This kind of writing – writing with a kind of brutal emotional honesty – is uncomfortable because we feel a bit like we’re undressing in public. It’s a bit like living out one of those stress dreams we’ve all had where we walk into a crowded room, stark naked.

But, in a way, that’s what we’re doing. We’re revealing our essence, exposing our soul.

Yes, of course, we translate these experiences into the language of the story. Your dad coming home drunk and beating you becomes the protagonist’s betrayal by their best friend. It’s not the same thing, but that’s the point. We use the real emotions we have from the actual events of our lives but attach them to fictional events.

That’s how we bleed.

That’s it! What do you think? Is this what the author of this quotation (“Writing is easy, just ...”) meant by opening a vein? Perhaps they were only trying to say that writing is a painful, exhausting experience.

Whatever the case, till next week, good writing!