Let’s talk about what suspense is. Sure, yes, we know what it is in a “I know it when I feel it” kind of way, but if we want our stories to create suspense in our readers, it would be helpful to have a definition.

Lee Goldberg once said that, "Suspense is an escalating sense of apprehension or fear, a building of pressure, heading either towards an uncertain conclusion or a horrifyingly certain one." [1]

I will look at two ways of creating suspense. First, the author might get a reader to ask a question without immediately answering it. We’re human, and once we have an interesting puzzle we find it difficult to NOT try to solve it. Second--and this is really just a more specific way of creating a question in the reader’s mind--the author might give the reader either more or less information than the hero. Let’s look at each of these techniques in turn.

Ask a Question but Withhold the Answer

Lee Child holds that suspense boils down to asking a question and making people wait for the answer. He believes that humans are wired to want the answer to a question they don't know the answer to.

Want viewers to stick around during a commercial break? Ask them a question before the break and answer it when the break is over. This is Child's explanation for his view that “The way to write a thriller is to ask a question at the beginning, and answer it at the end." [2]

Child also talks about his technique in his New York Times article, "A Simple Way to Create Suspense." [3]

"As novelists, we should ask or imply a question at the beginning of the story, and then we should delay the answer.... Readers are human, and humans seem programmed to wait for answers to questions they witness being asked."

"Trusting such a simple system feels cheap and meretricious while you’re doing it. But it works. It’s all you need. Of course, attractive and sympathetic characters are nice to have; and elaborate and sinister entanglements are satisfying; and impossible-to-escape pits of despair are great. But they’re all luxuries. The basic narrative fuel is always the slow unveiling of the final answer."

Dramatic Irony and Suspense

In order to understand how to create and build suspense we need to understand dramatic irony. Why? Because dramatic irony can be used to increase the audience's (and in this case our reader is our audience) sense of curiosity and concern for the hero.

An Example

Scenario 1: Imagine a hero inching along a darkened path, oblivious to the deadly monster creeping up behind him, poised to strike.

Scenario 2: Imagine that, as before, our hero inches along a darkened path but now there is no deadly threat stalking him. Instead, he is anticipating a threat just around the bend. He doesn’t know a monster is there, but he thinks one could be.

The first scenario creates suspense by giving the audience more information than the hero possesses. We see the danger creeping up on him and want to scream: Turn around!

In the second scenario we, the audience, know what the hero knows and, with him, we cringe as he rounds every corner, every bend in the twisty road.

That was a quick overview. I go over these points again, below.

Some Aspects of Dramatic Irony

Surface meaning versus underlying meaning

Dramatic irony occurs when the surface meaning of an utterance is at variance with its deeper meaning. In other words, dramatic irony depends upon certain people knowing more than others. Some who hear the utterance will be stranded at the surface while others will go deeper.

Let's look at the possibilities.

The audience knows less than one or more of the characters.

Tension can be generated when we see a character's reaction to, for example, the contents of a suitcase even though we never find out what it contained.

This example comes from Pulp Fiction. Vincent Vega looks into the suitcase, its eerie illumination playing over his face. For a moment Vega seems lost in whatever he sees. The viewer doesn't know what's in the suitcase, but Vega and his partner, Jules Winnfield, do. Vega is looking right at it but, damn him, he's not telling!

The audience knows more than one or more of the characters.

I think this is the far more common scenario. It happens on almost every show I watch, nearly every episode.

A character knows less about something than another character, and they don't know they know less.

For example, a couple of months ago I re-watched the science fiction and horror classic Alien, a movie that has aged remarkably well. At one point one of the characters, Brett, searches for Jones the cat. Everyone on the ship is going back into stasis and that includes Jones, but Brett needs to catch him first. Yes, sure, the alien is on the loose, but in this scene Brett isn't overly worried about meeting the alien since he knows Jones is in the area and, therefore, attributes any weird noises to the spooked feline.

Brett hears a noise, looks beneath nearby machinery and spots the cat. Brett tries to coax the cat out of his hiding spot but, just as the cat walks toward him, we see a tentacle unfurl behind Brett. Jones sees this, hisses and darts away. Brett is stunned. He thinks the cat hissed at him. Puzzled, he keeps calling Jones, trying to coax the cat out of hiding. While Brett does this we see the alien slowly, silently, unfurl behind him.

At this point in the movie, if you're anything like me, you grip the cushion you have a stranglehold on even tighter and scream: Turn around!

And, of course, Brett turns around but it's too late. He becomes monster chow.

This is the kind of thing we mean when we say that in dramatic irony the implications of a situation, speech, and so on, are understood by the audience but not by at least one of the characters in the drama. In this scene both the cat and the alien had more information than Brett did and, as so often happens in horror movies, Brett paid for that inequality with his life.

Unwise Behavior

When a passage contains dramatic irony, the character from whom information is being kept usually reacts in a way that is inappropriate and unwise.

In the example from Alien, running away and hiding would have been both appropriate and wise. Standing in front of the alien calling out "kitty, kitty," not so much.

Summary

To summarize, suspense is an escalating sense of apprehension or fear of a certain ending. Part of the reason this is effective is because it asks a question, “Will the hero survive?” and makes you wait for an answer. Lee Child has spoken quite a bit about this way of creating suspense. Dramatic irony is another way of creating suspense and it occurs when there is an incongruity between what the expectations of a situation are and what is really the case.

Notes

1. For more on this see the Google+ Hangout Libby Hellman hosted, "Secrets To Writing Top Suspense."

2. Lee Child was quoted having said this in an article about Thrillerfest, but I can't find the reference.

3. "A Simple Way to Create Suspense," by Lee Child (2012)

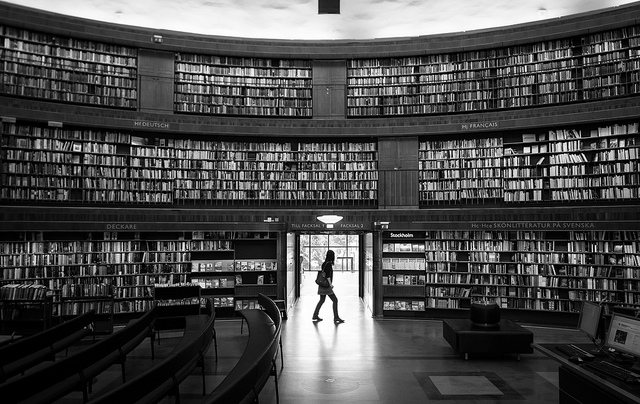

Photo Credit

Indiana Jones and the Mountain of Rocks, by JD Hancock. I altered the image to create a greater contrast with the text. I highly recommend dropping by JD Hancock's website and viewing his many, fascinating creations.

-- --

Other posts in this extended series (I'm blogging a book):

How to Write a Genre Story: The Index

Where you can find me on the web:

Twitter: @WoodwardKaren

Pinterest: @karenjwoodward

Instagram: @KarenWoodwardWriter

YouTube: The Writer's Craft