In a recent post Nathan Bransford talked turkey about Point of View.

First Person

In the first person perspective everything that happens in your story is told through your narrator's perspective. For example:

"Ouch! That hurt," I yelled. Jan glanced back and grinned.Nathan Bransford says this of it:

"Oh, I'm sorry, was that your foot?" she said.

I glared at Jan's back as she peddled off into the distance, laughing maniacally. She would pay. Oh, yes, she would pay.

The really compelling first person narrators are the ones where a unique character is giving you their take on something that is happening, and yet it's clear to the reader that it's not the whole story. You're getting a biased look at the world, which is central to the appeal of the first person narrative. [1]For example, in Jim Butcher's Dresden Files series each story is told by Harry Dresden, Chicago's only consulting wizard. As a result, the books are infused with his personality. A very good thing! But the reader doesn't know whatever Harry doesn't know and sometimes that's quite a lot; enough, certainly, to keep the story interesting.

Nathan Bransford suggests that if you use the first person prspective that you make your character likeable. Or at least likable enough to pass the "stuck in an elevator" test. He writes:

Would you want to be stuck in a room with this person for six hours? Would you want to listen to this person give a speech for six hours? If the answer is no, then you might want to reconsider. [1]

Third Person: Limited Versus Omniscient

In the third person perspective, limited, you are, as the name implies, limited to one person's point of view while in the omniscient mode you can peek into the minds of all your characters and report what you find. While the latter is VERY convenient it's not as personal.

Here's an example of third person limited:

"Ouch! That hurt," Karen yelled. Jan glanced back and grinned.It's not quite as personal because you're not hearing Karen's thoughts first hand, you're being told them by someone else.

"Oh, I'm sorry, was that your foot?"

Karen glared at Jan's back as she peddled off into the distance, laughing maniacally. Karen decided that Jan would pay for defiling the pristine newness of her sneakers.

In third person omniscient you can dip inside the head of anyone in the scene.

The Choice: Do You Want To Head-Jump?

Nathan Bransford writes that the decision whether to use third person limited or third person omniscient comes down to whether you want to head-jump. He writes:

Third person limited is, well, limited. The perspective is exclusively grounded to one character, unless you cheat a little. This means that you have all of the constraints of first person (all the reader sees is what the protagonist sees), but with just a tad more freedom. The reader will wonder a bit more precisely what that character is thinking and there's a bit more of an objective sensibility.He ends by saying:

One of the classic third person limited narratives is the Harry Potter series, and Rowling strays from Harry's perspective in only a tiny few rare instances. She therefore had to bend over backwards to filter everything the reader needed to know about that world through Harry's view. If Harry can't see it? It doesn't happen for the reader.

I would wager my sorting hat that things like the invisibility cloak and the pensieve were extremely inventive ways around the narrative challenges posed by third person limited. There is no "offstage" for the reader to witness something that Harry can't see, so instead he has to be present to see he shouldn't (invisibility cloak) and witnessing historical events for himself (pensieve).

Third person omniscient is, ostensibly, a bit more freeing, because you aren't limited to a single character's perspective. However, it's also very difficult because for a reader it's very disorienting to head-jump. If you're inside one character's head and then jump to the next character's head and then another, it's very difficult for the reader to place themselves in a scene. They just have whiplash. [1]

That's the key: Whatever perspective you choose, it has to be grounded. The reader has to know where they are in relation to the action so they can get their bearings and lose themselves in the story.Nathan Bransford's entire post is well worth reading--heck, all his posts are!: Third Person Omniscient vs. Third Person Limited.

Other articles you might like:

- David Mamet On How To Write A Great Story- How To Earn A Living As A Self-Published Writer

- Using Pinch Points To Increase Narrative Drive

Referenced articles:

1) First Person vs. Third Person, Nathan Bransford

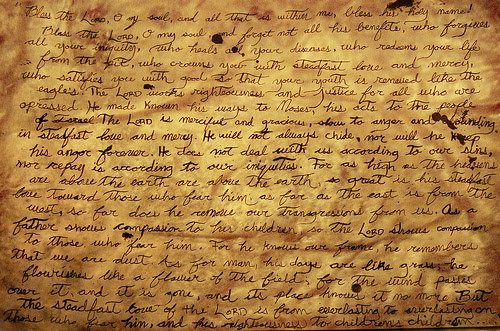

Photo credit: "Writing" by ^ Missi ^ under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0.