"If science fiction is escapist, it's escape into reality," Isaac Asimov

"... writing is survival. Any art, any good work, of course, is that," Ray Bradbury.

Ray Bradbury's, Zen In The Art Of Writing, is soul food.

I love Ray Bradbury's writing. Something Wicked This Way Comes had a profound influence on me as a young writer--but for some reason, even though it was recommended again and again, I neglected to read Ray Bradbury's book on writing.

That, I realize now, was a mistake.

How To Keep And Feed A Muse

The chapter I'm reading at the moment is How to Keep and Feed a Muse. Mr. Bradbury gives some remarkably detailed advice.

What To Feed Your Muse

1. A lifetime of experiences.

We must feed ourselves on life.

It is my contention that in order to Keep a Muse, you must first offer food. How you can feed something that isn't yet there is a little hard to explain. But we live surrounded by paradoxes. One more shouldn't hurt us.

The fact is simple enough. Through a lifetime, by ingesting food and water, we build cells, we grow, we become larger and more substantial. ...

Similarly, in a lifetime, we stuff ourselves with sounds, sights, smells, tastes, and textures of people, animals, landscapes, events, large and small. We stuff ourselves with these impressions and experiences and our reaction to them. Into our subconscious go not only factual data but reactive data, our movement toward or away from the sensed events.

These are the stuffs, the foods, on which The Muse grows.

2. Read poetry every day.

What kind of poetry? "Any poetry that makes your hair stand up along your arms. Don't force yourself too hard. Take it easy."

3. Books of essays.

You can never tell when you might want to know the finer points of being a pedestrian, keeping bees, carving headstones, or rolling hoops. Here is where you play the dilettante, and where it pays to do so. You are, in effect, dropping stones down a well. Every time you hear an echo from your Subconscious, you know yourself a little better. A small echo may start an idea. A big echo may result in a story.

. . . .Why all this insistence on the senses? Because in order to convince your reader that he is there, you must assault each of his senses, in turn, with color, sound, taste, and texture. If your reader feels the sun on his flesh, the wind fluttering his shirt sleeves, half your fight is won. The most improbable tales can be made believable, if your reader, through his senses, feels certain that he stands at the middle of events. He cannot refuse, then, to participate. The logic of events always gives way to the logic of the senses.

4. Read short stories and novels.

Read those authors who write the way you hope to write, those who think the way you would like to think. But also read those who do not think as you think or write as you want to write, and so be stimulated in directions you might not take for many years. Here again, don't let the snobbery of others prevent you from reading Kipling, say, while no one else is reading him.

How To Keep Your Muse

Ray Bradbury advises that not only should we write every day, but that we should write 1,000 words a day for 10 or 20 years!

Great advise. Truly excellent. Myself, though, I hope it doesn't take 20 years! Of course, if it does, it does. Writing is the kind of thing that, if one can be discouraged from it, one probably should be.

And while feeding, How to Keep Your Muse is our final problem.

The Muse must have shape. You will write a thousand words a day for ten or twenty years in order to try to give it shape, to learn enough about grammar and story construction so that these become part of the Subconscious, without restraining or distorting the Muse.

By living well, by observing as you live, by reading well and observing as you read, you have fed Your Most Original Self. By training yourself in writing, by repetitious exercise, imitation, good example, you have made a clean, well-lighted place to keep the Muse. You have given her, him, it, or whatever, room to turn around in. And through training, you have relaxed yourself enough not to stare discourteously when inspiration comes into the room.

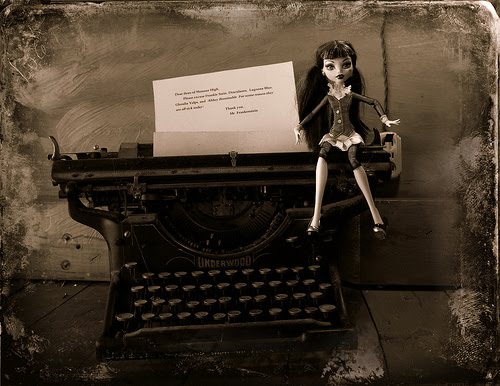

You have learned to go immediately to the typewriter and preserve the inspiration for all time by putting it on paper.

Miscellaneous

Do not, for money, turn away from all the stuff you have collected in a lifetime.

Do not, for the vanity of intellectual publications, turn away from what you are—the material within you which makes you individual, and therefore indispensable to others.

. . . .

Who are your friends? Do they believe in you? Or do they stunt your growth with ridicule and disbelief? If the latter, you haven't friends. Go find some.

# # #

I haven't contributed a lot of commentary, above, because ... well, what could I add? One thing Mr. Bradbury said--I didn't include the quotation--was that he wrote 3,000,000 words before his first story was accepted at the age of 20.

Three million words!

Add to that, Mr. Bradbury wrote every day, every single day. He must have had a well fed, and very content, muse.

What is your favorite book on writing? What is the best writing advice you've received?

Other articles you might like:

- Fleshing Out Your Protagonist: Creating An Awesome Character- Dean Koontz And 5 Things Every Genre Story Needs

- How Plotting Can Build A Better Story

Photo credit: "Dust" by Robb North under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0.