What follows is a structure—one-among-many—a murder mystery could have. If you would like to read about a general story structure head over here: The Structure of a Great Story: How to Write a Suspenseful Tale!

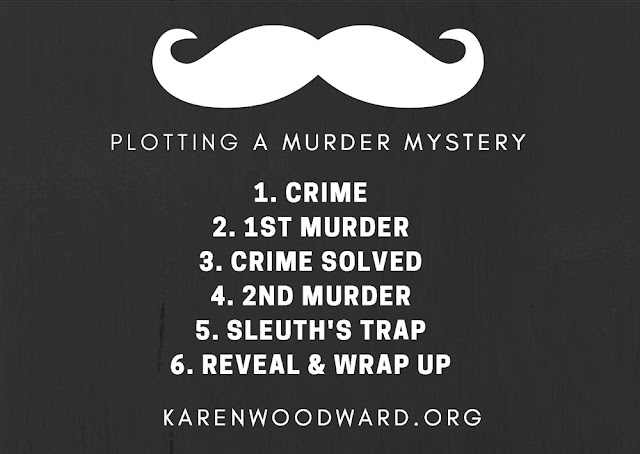

Below, I’ve broken a murder mystery into six main events stretched over five acts.

A Murder Mystery in Six Events

1. A Crime

2. 1st Murder

3. Crime solved

4. 2nd Murder

5. Sleuth’s Trap

6. Reveal & Wrap Up

I'll discuss each of these in more detail in what follows.

Again, I want to stress that I’m not saying this is how all murder mysteries are structured, simply that this is one way a murder mystery could be structured.

A Murder Mystery in Five Acts

Act One: The Crime, Murderer Introduced and the 1st Body Found

Opens with: The Crime.

The Crime. In the first act a crime occurs and is the inciting incident for that act (not the main story). The crime is not the first murder. It could be blackmail, common assault, burglary, vandalism, etc. Your detective could investigate this crime or someone else might. For instance, if your detective works as a homicide detective this would be outside her purview. Or if your detective runs a bake shop this particular crime might involve those close to her, but not involve her directly.[1]

The Murderer is introduced. The murderer doesn’t have to be introduced in Act One, but I think it’s a good idea. If you don’t introduce the murderer here try to at least have one or more of your characters mention him or her in conversation.

The 1st Body. At the end of Act One we have the Inciting Incident for the main arc of the story: The first body is discovered. This event draws the detective into the story.

Close with: Finding the 1st body.

Act Two: Detective Introduced and Led Astray

Opens with: The detective. Perhaps the detective is at the crime scene or at the morgue. Generally I think it works best if the detective is introduced with the victim since it was the victim who, in a sense, called him into the story. It is the victim the detective seeks justice for.

Detective Introduced. The detective and her sidekick/helper are introduced and interview the suspects. They will likely also talk to one or two experts over the course of the story.

Led Astray. Initially, the murder leads the detective astray. Gives them a red herring. As a result of this, the murderer gains the upper hand. (The detective likely won't realize this is the case until after the second body is found.)

2nd body found. The detective feels he is partially responsible for this person’s death. Perhaps he suspected this person wasn’t telling him everything but he didn’t press her because she seemed frail and elderly, or perhaps the sleuth and this person had a relationship.

Closes with: The second body is discovered.

Act Three: Crime Solved and the Detective Knows Who the Killer Is

Begins with: The detective at the crime scene or in the morgue. He discusses with his helper/sidekick how the death changes things, his current theory of the crime, and so on. This is a low point for the detective. The murderer has the upper hand.

New information sets the sleuth on the right track. We’re at the midpoint now and this storyline should resolve and loop back into your main arc. This will have the effect of giving the detective a major revelation into either the circumstances of the first murder or the murderer himself/herself. At this point the detective gets information that gives him a whole new perspective on the case.

Crime Solved. The detective uses the information, his increased knowledge, to solve the initial crime. The detective is back on his game and the murderer is nervous.

Detectives figures out the identity of the murderer. Detectives figures out the identity of the murderer. This act ends with the detective at a high point. He has solved the initial crime and this resolution combined with something his sidekick says (it doesn't have to be this, though it often is), allows him to identify the murderer. The detective also, often, knows how the murderer pulled it off, he just doesn't have any proof.

Ends with: The detective solving the crime.

Act Four: Third Body Found; Sleuth Lays a Trap for the Killer; The Reveal

Begins with: The sleuth puts into action a plan to trap the killer.

Act Four begins with a sequel. We need to all be on the same page. The sleuth is about to keep something from Watson, which means he’s going to keep something from the reader. We need to be sure not to trick the reader, not to keep anything back. All the clues need to be on the table at this point.

The Third ‘Murder.’ There really is no third murder. This is a trap the detective lays for the killer. Perhaps the murderer wants to kill the sleuth and the sleuth fakes his death. Perhaps the sleuth gets an accomplice to blackmail the killer and the killer takes the bait and appears to murder the blackmailer (or perhaps the murderer is apprehended before he or she can do the deed; if this is the case then it also serves as The Reveal).

The Reveal. The murderer thinks he’s in the clear, he’s gotten away with it. Everyone is in the library sipping brandy and pulling a long face. The detective says, “Well, at least I now know who committed the crimes.” The real killer thinks the detective is a fool and plays along.

The detective begins to lay out all the clues, explaining things as though he is still fooled by the murderer. Then he explains why the person the murderer was framing couldn’t have done it.

This makes everyone nervous. What is the detective talking about? What he’s suggesting is impossible! We know the victims were murdered, but the detective has ruled everyone out!

Then the detective says: No. The killer was clever, yes, but he was up against me, the great one! He never had a chance. The detective then goes on to explain what the real killer's plan was, what his motives where and how he did what he did.

The killer now feels like a cornered animal, fighting for its life. He passionately denies everything. "No, this is impossible! This is outrageous!"

But then comes the final detail, the final twist. The third victim isn’t dead! It had been a trap all along! The killer, panicked, springs up ready to run but is overpowered by the detective’s helper and the rest of the suspects.

Ends with: The reveal. The detective reveals the killers identity.

Act Five: The Wrap Up

Begins with: The detective explains how he discovered the identity of the murderer and ties up all the loose ends.

Finish explaining the clues. The first part of the wrap up deals with any unresolved details, any unanswered questions from the reveal. You can take a bit of time here.

Resolve the relationship arcs. The second part of the wrap up deals with relationship arcs, resolving them and tying them off. Make sure the detective and his sidekick, their conflict, is resolved right before the end.

Ends with: The detective, having wrapped up all the relationship arcs, goes back to his ordinary life.

* * *

I want to stress again that this is just one of thousands of possibilities for how you could structure a murder mystery.

Every post I pick something I love and recommend it. This serves two purposes. I want to share what I’ve loved with you, and, if you click the link and buy anything over at Amazon within the next 24 hours, Amazon puts a few cents in my tip jar at no cost to you. So, if you click the link, thank you! If not, that’s okay too. I’m thrilled and honored you’ve visited my blog and read my post.

Witness for the Prosecution, by Agatha Christie.

This is, hands down, one of the best plotted stories I have ever read! If you’ve never seen it before—I believe it started out life as a play—read it! Or, if you like, watch the 1957 movie of the same name. Don’t let anyone tell you the ending, though! It’s one of the best endings of a mystery story, ever!

From the blurb: “When wealthy spinster Emily French is found murdered, suspicion falls on Leonard Vole, the man to whom she hastily bequeathed her riches before she died.”

That’s it! I have another post nearly finished, one that picks up some of these same themes. In the meantime, good writing! :-)

Notes:

1. Above, I suggested beginning your murder mystery with a run-of-the-mill crime but there's another way to approach this, a way that can increase the stakes and start things off with spine-tingling excitement: Show the murder happening. The body, though, is still found at the end of the first act.