This was going to be a post about critiquing with a short introduction about what we mean--or what I mean--by "good writing". That post turned into the first of a two part series on critiquing!

Today I'll discuss what makes a story good. Or, more to the point, what can keep a story from being good. Tomorrow I'll talk about how to critique a story, or at least how I do it.

The Difference Between "I like it" and "It's good"

Everyone has their own idea of how to critique. If something I mention resonates with you, great! Use it. If it doesn't, that's fine. Forget it.

Use what works for you.

A critique is, at its core, an evaluation. An appraisal. But in order to appraise we must have a measure. For instance, in order to say whether a man is too fat or too thin we must know the correct weight for a man of his age and height.

But evaluating a story is very different from evaluating weight. Saying whether a man is too thin or too fat belongs to medical science but writing is an art. And the arts do not admit of the same kind of measure.

This doesn't mean writing can't be evaluated, it means the metric for evaluation isn't objective in the same way as it is for science. I think that, like beauty, the worth of a story, the value of a story, resides in the eye of the beholder.

Example: Movies

What do you think? If you disagree with me, let me try and persuade you. Think of a movie you loved. Chances are, if you picked 10 random people out of a crowd at least two of them wouldn't even like that movie.

Does that mean you're wrong to love that movie? Does it mean you were foolish to spend your money to see that movie? No! Of course not. Tastes differ.

Even great works of literature like "The Picture of Dorian Gray" by Oscar Wilde have their detractors.

In fact, I would go so far as to claim that for any creative work you'd care to name, there will be folks--sane, reasonable people--who don't like it.

And that's fine. That's the nature of art.

Why Bother With Critiques If It's All Relative?

You might wonder, if the worth of a story really is in the eye of the beholder, why do we bother with critiques? Isn't it impossible to say, "That story is good" or "That story is bad"?

Yes and no.

We know what we like. We know whether a story was interesting, whether it was difficult to read, whether we were able to suspend our disbelief (whether we 'bought the premise'), whether it made us feel inspired.

And, in certain ways, humans are pretty similar in what they like and dislike.

It's All About Emotion

Really, what are we asking for when we give someone a story to critique? Scratch that. What is it that we, as storytellers, want to know? We want to know whether the story grabbed that person's attention. Whether it rocked their world. Whether it made them feel something. Anything!

As Stephen King said in a recent talk to a group of students at the University of Massachusetts:

“I’m a confrontational writer. I want to be in your face. I want to get into your space. I want to get within kissing distance, hugging distance, choking distance, punching distance. Call it whatever you want. But I want your attention.” (Stephen King: My mother-in-law scares me)Perhaps a better question than "Was the story good?" is "Did the story move you emotionally?", "Did it grab you?"

I used this quotation from Chuck Wendig in my article yesterday about how to create a great antagonist, but it's so good I'm going to use it again:

I hate that I love Hans Gruber. I love that I hate every Nazi in every Indiana Jones movie. For #$%$’s sake, make me feel something. (25 Things You Should Know About Antagonists)So what we need to ask is whether there is anything that a story needs to have in order to elicit emotion. Is there some one thing that is absolutely essential for a story to stir the emotions of readers?

I don't think so.

Now hold on, don't throw anything at me yet!

There are some things that will turn readers off, that will prevent your stories from eliciting emotion. We'll take a look at those in a moment but first I have to tell you what writing really is:

Writing is telepathy.

Writing Is Telepathy

If you think I've gone completely batty you can blame Stephen King. It's his analogy from On Writing.

I hope Mr. King will forgive me for quoting extensively from his book but this is a terrific concept every writer needs in their toolbox.

And here we go—actual telepathy in action. You’ll notice I have nothing up my sleeves and that my lips never move. Neither, most likely, do yours.

Look—here’s a table covered with a red cloth. On it is a cage the size of a small fish aquarium. In the cage is a white rabbit with a pink nose and pink-rimmed eyes. In its front paws is a carrot-stub upon which it is contentedly munching. On its back, clearly marked in blue ink, is the numeral 8.

Do we see the same thing? We’d have to get together and compare notes to make absolutely sure, but I think we do. There will be necessary variations, of course: some receivers will see a cloth which is turkey red, some will see one that’s scarlet, while others may see still other shades. (To colorblind receivers, the red tablecloth is the dark gray of cigar ashes.) Some may see scalloped edges, some may see straight ones. Decorative souls may add a little lace, and welcome—my tablecloth is your tablecloth, knock yourself out.

.... The most interesting thing here isn’t even the carrot-munching rabbit in the cage, but the number on its back. Not a six, not a four, not nineteen-point-five. It’s an eight. This is what we’re looking at, and we all see it. I didn’t tell you. You didn’t ask me. I never opened my mouth and you never opened yours. We’re not even in the same year together, let alone the same room … except we are together. We’re close.

We’re having a meeting of the minds.

I sent you a table with a red cloth on it, a cage, a rabbit, and the number eight in blue ink. You got them all, especially that blue eight. We’ve engaged in an act of telepathy. No mythy-mountain shit; real telepathy. (Stephen King, On Writing)

Good And Bad Transmissions

Think of an old-fashioned radio. There are two reasons my grandparents turned off their radio.

Static. If there was a lot of static then whatever was being transmitted, music for instance, sounded horrible. The radio would get turned off even if it was playing everyone's favorite song.

Boring. If no one liked the song the radio would get turned off even if the signal was clear as a bell.

This corresponds to the two major ways stories can go wrong:

1) Static = Unusual grammar and infelicitous word choice

2) Boring = Boring

How To Test For Static

Unsure if a certain word or sentence or scene is static? Ask: If I removed it would the meaning be unchanged?

a) The cat was very fat.

b) The cat was fat.

I prefer (b).

As for sentences and scenes, ask whether they push the story forward. If they do, great! If they don't, cut them. Kill your darlings.

Unusual Grammar Adds Static

Writers sometimes consciously decide to not use correct grammar--in dialogue for instance--because this can help communicate something about the speaker.

That said, in general, the rules of grammar are there for a reason. If you follow them your writing will be clearer and easier to understand than if you don't.

Clear writing = no static.

Clear writing is good.

Anything that prevents your writing from being clear is bad. Why? Because, continuing with my radio analogy, it adds static to the signal and makes it harder to hear the song.

Infelicitous Word Choice Adds Static

Every writer has their bugaboos, their pet peeves. These are mine:

Very unique

- "Unique" doesn't admit of degrees. Either a thing is unique or it isn't.

- "Very" is an adjective that, generally speaking, can be taken out of a sentence without changing its meaning.

Decimate

- "Decimate" is not a synonym for "obliterate".

English is my first language and yet I am continually learning, continually amazed by the complex and evolving nature of language--and of my often frail grasp of it. Everyone makes mistakes.

Remember, even if there is a tiny bit of static in the channel folks aren't going to turn off the radio as long as they like the song.

Creating A Clear Channel

I've compared writing to a transmission, or to the channel through which a transmission is made, and discussed various ways the signal can degrade.

Now I'd like to talk about clear channels; zero static transmissions.

I'd love to be able to say, "If you do this and that and the other thing, then your writing will be awesome. But then, of course, machines could do it and we'd all be out of work!

No, the best I can do is give you examples of writing that reaches into my soul and makes me want to write like that.

Neil Gaiman, M Is For Magic

Stories you read when you’re the right age never quite leave you. You may forget who wrote them or what the story was called. Sometimes you’ll forget precisely what happened, but if a story touches you it will stay with you, haunting the places in your mind that you rarely ever visit.

Horror stays with you hardest. If it brings a real chill to the back of your neck, if once the story is done you find yourself closing the book slowly, for fear of disturbing something, and creeping away, then it’s there for the rest of time.

Ernest Hemingway, Hills Like White Elephants

The hills across the valley of the Ebro were long and white. On this side there was no shade and no trees and the station was between two lines of rails in the sun. Close against the side of the station there was the warm shadow of the building and a curtain, made of strings of bamboo beads, hung across the open door into the bar, to keep out flies. The American and the girl with him sat at a table in the shade, outside the building. It was very hot and the express from Barcelona would come in forty minutes. It stopped at this junction for two minutes and went to Madrid.

‘What should we drink?’ the girl asked. She had taken off her hat and put it on the table.

‘It’s pretty hot,’ the man said.

‘Let’s drink beer.’

‘Dos cervezas,’ the man said into the curtain.

‘Big ones?’ a woman asked from the doorway.

‘Yes. Two big ones.’

The woman brought two glasses of beer and two felt pads. She put the felt pads and the beer glass on the table and looked at the man and the girl. The girl was looking off at the line of hills. They were white in the sun and the country was brown and dry.

‘They look like white elephants,’ she said.

If you haven't re-read Hills Like White Elephants recently, perhaps you'd like to. I just did, it took me five minutes. Each time I read it that story amazes me. Especially how I know what the characters are talking about even though they never say it. That story is all about subtext, about what is not being said. Brilliant.

As I wrote at the beginning, this was going to be a post about how to critique prefaced by a brief discussion of the nature of stories. (Sigh) I really do have trouble writing short!

I'll talk about critiques and critiquing tomorrow. Till then, happy writing! :-)

Update: Here's a link to The Dark Art Of Critiquing, Part 2: Formulating A Critique

Other articles you might like:

- 12 Tips On How To Write Antagonists Your Readers Will Love To Hate- Editing & Critiquing

- The Albee Agency: Writers Beware

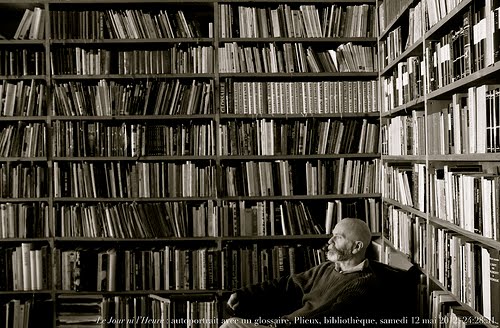

Photo credit: "Le Jour ni l’Heure 2225 : autoportrait avec un glossaire, Plieux, bibliothèque, samedi 12 mai 2012, 24:28:31" by Renaud Camus under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0.

THANK YOU! This is awesome. I've been struggling with this very thing.

ReplyDeleteThanks Leauxra! I'm glad it made sense. :-)

Delete