Today I'm going to do what I promised yesterday and step us through the rest of our five paragraph summary of the journey of your Hero and his band of intrepid adventurers.

Below are links to the previous articles in this series, something I'm calling The Starburst Method, though I've been thinking of changing the name to something more descriptive. The Sculpting Method or perhaps The Diamond Method.

Since this article is a continuation of the last two (The Starburst Method: The Hero's Journey), you may want to give them a quick read.

1. The Starburst Method: What It Is And What It Can Do

This gives a roadmap of where we're going and why we want to get there.

2. The Starburst Method: Discovering Your Characters

We begin to get to know our characters, what they want, what they fear, what they do for a living, what their dreams are and, most importantly, what their goal is.

3. The Starburst Method: The Hero's Journey, Part 1

Here we go deeper into our characters and start transforming our knowledge into a narrative. We hone what we know about our characters until it can be expressed in five paragraphs that summarize our hero's journey.

4. The Starburst Method: The Hero's Journey, Part 2

A continuation of the ideas in (3).

Let's dive right in!

4. It All Falls Apart

Here we meet our antagonist.

Of course your antagonist has been around, in story terms, for some time. Probably ever since you entered the Special World. In fact, he was likely one of the first people your hero met, or heard about, when he entered the Special World. This is just the first time we're meeting him in our summary of your hero's journey.

Also, when I say it all falls apart I'm not talking about The Dark Night of the Soul or The All Hope Is Lost point that usually occurs about 3/4 of the way through a story. The 'All Hope is Lost' point occurs when the hero and his intrepid band of adventurers lumber up to the climax of the story and their Big Plan falls apart.

No, what I'm talking about here is the first sign of trouble. The first real resistance they face in the Special World. (Some would also call this a pinch point.)

For instance, in The Firm everything seems to be going great--Mitch McDeere, the protagonist, has a nice house, great car, awesome paycheck and he's on the fast track to becoming partner--then he discovers that the law firm he works for, Bendini Lamert & Locke, is a front for organized crime and he's in it up to his eyeballs.

At that moment Mitch's initial goal of becoming a wealthy lawyer dissolves and he gets his true goal, the Story Goal: Get away from the mob with his licence to practise law, and his marriage, intact.

This leads us to ...

5. The Challenge

How is our intrepid adventurer going to thwart the machinations of the antagonist? How is your hero going to get himself, and his friends, out of this big fat mess?

That's the story goal, the challenge. That's what we want to read about and it will form the heart of your story. (I feel as though there should be a drum roll at this point because, in a way, this is what the entire series has been leading up to.)

Yes, there will be hurdles the hero must jump, dangers to avoid, tests to pass--although he should fail at least one, and fail spectacularly--and so on, but it's all because of the hero's goal and the mess he's gotten himself and his friends into.

And why has he gotten himself into that mess? Because of who he is, because of what he wants, because of his Dream and, especially, his Goal.

An Example: The Firm

Yesterday I gave you an example of a five paragraph summary based on Star Wars IV: A New Hope, today I'll give you another. This one is based on The Firm.

1. Ordinary worldBy the way, I took that example from an earlier post I wrote: The Structure Of Short Stories: The Elevator Pitch Version.

Mitch McDeere worked hard to get top grades at Harvard Law School because he never wanted to be poor again.

2. Characters and setting

Mitch would never have succeeded without the love and support of his beautiful wife Abby who, more than anything, wants him to stop running and accept who he is, and to accept his brother, even though his family is a reminder of what Mitch is running from: the shame of growing up in a trailer park, poor, raised by a mother who didn't really care about him.

3. Entering the special world

When the lawyers from Bendini, Lambert & Locke offer Mitch more money than any other law firm it is a dream come true and he and Abby move into their brand new house, courtesy of the firm.

4. It all falls apart

Everything is great until Mitch learns about the secret files and discovers Bendini, Lambert & Locke is just a front for organized crime. As the FBI closes in on Mitch, threatening him with prison, the mob gets suspicious.

5. The challenge for the protagonist

Mitch has to rely on his wits to save himself and Abby. But is he up to the challenge?

What you have at this point--a five paragraph story summary--can form the skeleton of your story. We've met the main characters, or at least their archetypes. They need fleshing out and, as a result, your story skeleton will grow, change, bend, but as long as it remains roughly 'story shaped' (i.e., focused on the hero's goal, the hero's journey) it's all good.

To Be Continued

In our next and final section we'll look at condensing your story down into one or two sentences.

This is handy for two reasons:

a) You'll be able to determine what is really truely important in your story, and

b) If you ever have to write a pitch, you'll have your tag-line ready!

At this point, with your five point summary concluded, you already have a blurb for your book or the start of your pitch.

Update: Here is a link to the final installment of this series: The Starburst Method: Summarizing Your Story In One Sentence

Other links you might like:

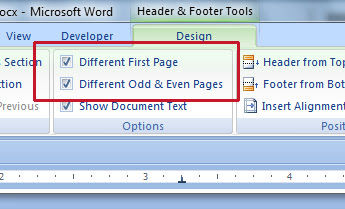

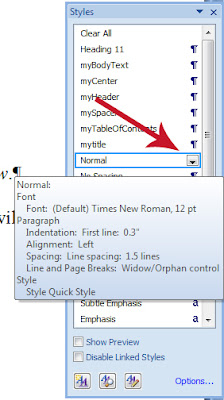

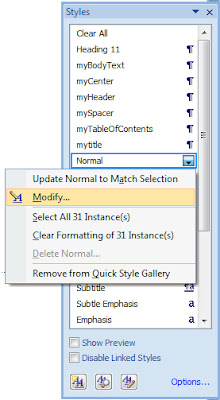

- How To Format A Word Document For Uploading To Amazon: MS Word Styles- The Starburst Method: The Hero's Journey, Part 2

- The Magic Of Stephen King: How To Write Compelling Characters & Great Openings

Photo credit: "Fire Storm" by JD Hancock under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0.